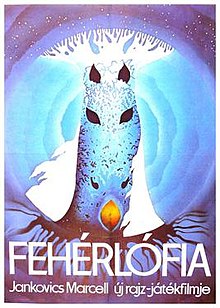

Son of the White Mare

(1981, Ages 16 and Up)

9/2/22

It sometimes saddens me that America, being such a comparatively young nation, doesn’t have its own mythology the way other older cultures do. Sure, we have our tall tales: Paul Bunyan, Johnny Appleseed, John Henry and the like. But I wouldn’t go so far as to place Darth Vader, Yoda, Batman, Superman and Spider-Man on the same pedestal as Zeus, Odin, Shiva, Anubis, and Kukulkan. With all due respect to the former, and despite their wild popularity and influence, I think it may be because they feel too modern and commercialized to me. True mythological figures, in my mind, are ancient and omniscient forces of nature, not only providing (supposed) explanations for why the world is the way it is now, but existing in a dreamlike time and space beyond mankind’s reach and earthly comprehension. Thus, it is particularly enlightening to experience a mythological story expressed from the heart of its own native country, even if—or maybe especially when—it’s done via contemporary means.

A beautiful white mare goddess races for her life through a dark forest as her once glorious realm falls. Just as the evil minions in pursuit are about to claim her, the mare finds safe haven within a mighty hollow tree. It is here that she gives birth to a human boy, Treeshaker, who gains his godly strength from his mother’s milk. As he grows to manhood, the mare tells her son the story of the Sky King and Snow Queen, and their three princely sons who married three fairy princess sisters, Autumnfair, Springfair, and Summerfair. All would have been happy and prosperous, had the curious sisters not opened the one door forbidden to them. The three evil dragons, now freed, immediately captured the princesses, killed the princes, overthrew the King, and imprisoned the Queen. The Queen bore two sons, who disappeared; while pregnant with a third child, she escaped—in the form of a white mare. Understanding his birthright and his purpose, Treeshaker sets out to reunite with his long-lost brothers—Stonecrumbler and Irontemperer—and with them, journey into the Underworld in order to defeat the dragons, reclaim their brides, and restore their kingdom.

The plot of White Mare is based on the 1862 Hungarian folktale Fehérlófia, by László Arany, with director Marcell Jankovics giving at the beginning a dedication to “the Scythians, Huns, Avars, and other nomadic peoples.” Though Jankovics had wanted to make a fairytale movie from the start, his original vision couldn’t be realized due to the political tensions prevalent in the Cold War Eastern Europe in which he grew up. According to animation historian Charles Solomon in the Blu-ray’s booklet:

“A scholar of mythology and symbolism, [Jankovics] initially planned to meld several folktales into a feature that would explore the cycles of time and space. [. . .] But according to Marxist theory, time is irreversible. A film that focused on the recurring cycles that characterize many myths could be perceived as anti-Marxist by the Soviet-dominated government.

Instead, Jankovics turned to ‘The Son of the White Mare,’ an oral epic of Central Asia that was brought to Europe by the early Hungarians. Like all folktales, it exists in multiple versions (more than 50 variations have been collected by scholars in the Carpathian Basin), and the filmmaker drew elements from a half-dozen accounts of the story.”

For unknown reasons, the film wasn’t distributed in America upon release. Very strange, not to mention downright devastating, considering the factors that would have worked in its favor:

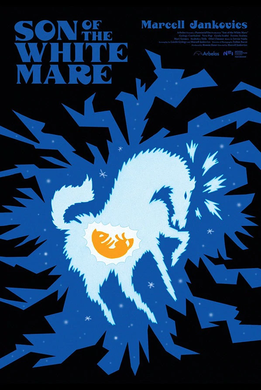

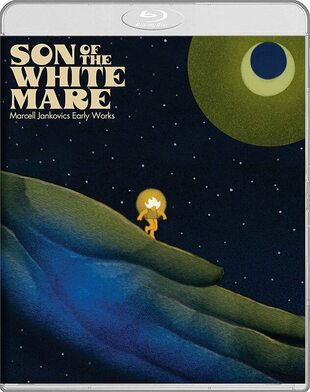

Still, White Mare did find success, being placed at #49 on the Olympiad of Animation in 1984 and premiering at the Los Angeles International Animation Celebration in 1985. Then, in 2019, LA studio Arbelos Films and the Hungarian Film Institute gave the movie a stunning 4K restoration, screening it at the 2019 Fantasia International Film Festival and planning a long-overdue theatrical release in the U.S. soon after. This plan was unfortunately shelved in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, so White Mare was instead made available to stream in America through Vimeo in late 2020, and then released on Blu-ray in 2021.

The “brave hero rescues damsel in distress from evil monsters” plot is pretty basic and antiquated on paper, but Jankovics makes it stand out by giving it a phantasmagoric 20th century coat of paint in every sense of the term. White Mare’s production and design was heavily influenced by the psychedelic drug culture of the 60’s, resulting in a piece meant to stun the senses and mystify the mind as well as entertain the eyes.

The music alone speak volumes (pun intended) of the alien world viewers are about to enter. Though the electronic soundtrack may seem better suited for equally surreal but more contemporarily-based movies like Labyrinth, Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, or 2001: A Space Odyssey, the synthesized ambience fits the mythological setting: dreamy and nightmarish all at once, completely transcendent of time, space, and all things mortal.

I think where Jankovics is at his most creative and clever is how he reimagines and enhances the story’s traditional fairytale tropes and symbols with his own unique artistic nuances, namely, his highly abstract design and heavy emphasis on vivid colors and symmetrical shapes. This is best portrayed by the three brothers, who are kind of like the incarnation of the Goldilocks concept of “too hot, too cold, just right”:

STONECRUMBER: [Nervously] Your Royal Highness, dear father . . . We were, uh, thinking . . .

IRONTEMPERER: [Rudely] Give us our fair share!

TREESHAKER: [Respectfully] Dear father and mother, our King and Queen. We would like to get married.

As is so with their polar opposite brides, and their adversaries, who, by the way, are not dragons in the traditional sense (I think of them more like golems myself, but that’s just me).

Stonecrumbler, the first-born, is colored in shades of coppery red with lots of teardrop-shaped curves (some more flattering than others). Such a design I believe fits his personality as a careless, hotheaded bumbler, slow in words and wit, with more rocks in his head than in his hands. These traits contrast the vein and sensual nature of his lusty, and dare I say, busty, destined bride, Autumnfair, while paralleling the Three-Headed Dragon, a crude, boorish oaf made of stone:

STONECRUMBLER: [Trembling after being pulled back up from the pit of the Underworld] There are so many nasty creatures down there, they almost pecked out my eyes. It was so dark, I couldn’t see my own hands.

--

AUTUMNFAIR: [Seductively to Treeshaker] What brought you here? No soul ever comes here.

TREESHAKER: [Awkwardly as she embraces him] I am here . . . I’ve come for you.

AUTUMNFAIR: [Suddenly pushes him away in disgust with a sneer] Oh just get lost, before my husband comes home. My husband is the three-headed dragon. And when he gets home, he’ll kill you.

--

THREE-HEADED DRAGON: Woman! I smell a stranger here. [. . .] Well then, let’s fight on the copper field!

Irontemperer, the middle brother, is a bit more competent than Stonecrumbler, though not by much. His triangular, silvery blue form represents an arrogance as cold and hard as the metal he molds like clay. His brashness is balanced out by his very needy and very whiny betrothed, Springfair; and her captor, the Seven-Headed Dragon, matches his aggression via the personification of war: a fully armed tank. (No, I’m not making that up):

IRONTEMPERER: [to Treeshaker as he finishes his sculpting his metal club] I will go with you, my friend. But first I want to know who is the strongest among us. [Increasingly aggressive] Who is going to lead us? Let’s wrestle!

--

SPRINGFAIR: [Terrified almost out of her wits] What brought you here? No soul ever comes here!

TREESHAKER: [Perfectly calm] I’ve come for you.

SPRINGFAIR: [Pushes him away, frantic] Oh just get lost, before my husband comes home. My husband is the seven-headed dragon. He can throw his club from seven miles. And when he gets home . . .

TREESHAKER: [Almost amused] . . . he’ll kill me, I know.

SPRINGFAIR: [Quiet now, but still fearful] Yes, he’ll kill you, right away.

--

SEVEN-HEADED DRAGON: Who’s here? I’ll tear him apart! [. . .] [To Treeshaker] You dog! You must die! My silver field is waiting for you.

And then there is Treeshaker, the youngest, and therefore, the kindest, bravest, and overall best, as is visually apparent from his hues of golden yellow and the sunlike spheres adorning his face. Some of his attractiveness is more subtle: his name and special ability symbolizing nature and life, as opposed to his brothers’ inorganic mineral names, and well as his modesty, as Stonecrumbler goes shirtless and Irontemperer’s smock covers only his front. Likewise, Treeshaker’s beloved, Summerfair, is more reserved and dignified than her sisters; and his enemy, the Twelve-headed Dragon, though his pixilated skyscraper form makes him look like a boss from a vintage Atari game, is nevertheless more terrifying and powerful than his brothers because of his intelligence and foresight:

TREESHAKER: [To his brothers] My dear brothers, my mother told me that the fairy princesses have been kidnapped by dragons. We must find the hole the dragons used to enter the Underworld. [. . .] [Addressing the golden castle] Castle, stop spinning! Or else, I’ll destroy you!

--

SUMMERFAIR: [With demure curiosity] What brought you here? No soul ever comes here.

TREESHAKER: [With true love] I’ve come for you.

SUMMERFAIR: [Embraces him] Oh, my sweet savior.

--

TWELVE-HEADED DRAGON: [With a booming malevolence] I know you, Treeshaker, Son of the White Mare. I’ve known ever since you were just a tiny fetus in your mother’s womb, that someday we would do battle. [. . .] You have killed two of my brothers. Even if you have a thousand lives, you’ll die for this. [. . .] Let’s see, then, how strong you are. Join me on the golden field.

Yet in spite of these obvious differences, I love the artistic touches which illustrate the warriors’ brotherly bond. Many shots cut or dissolve from one brother to another in such a way as to give the illusion that they are morphing into one another, while others show the circular ground rotating beneath them as they walk, as if their godly motion is what moves their entire world. And in one of the film’s most beautiful sequences, before beginning their journey, the trio swears their undying loyalty to each other by grasping hands around Irontemperer’s triangular club. Their linked arms dissolve into a flowing braid-like design as it rotates clockwise; the sides of the club multiply, changing it into a twelve-pointed sun, which in turn transforms into the brothers’ divine faces.

It’s movies like this that make both foreign animation and film as an art form so enthralling to me, not to mention remind me of the majesty and real-world significance of folklore. Jankovics not only turns what would otherwise be a very basic and clichéd story into a kaleidoscopic powerhouse of epic fantasy, but does so without diminishing its universal qualities or disparaging its noble heritage. I hope that many more hidden cinematic gems are found and polished so they may be given the admiration this cosmic jewel was once so sadly denied.

CREDITS:

All images, audio, and links belong to their respective owners; no copyright infringement is intended.

MAIN THEME:

“The Call” - Briand Morrison and Roxann Berglund

A beautiful white mare goddess races for her life through a dark forest as her once glorious realm falls. Just as the evil minions in pursuit are about to claim her, the mare finds safe haven within a mighty hollow tree. It is here that she gives birth to a human boy, Treeshaker, who gains his godly strength from his mother’s milk. As he grows to manhood, the mare tells her son the story of the Sky King and Snow Queen, and their three princely sons who married three fairy princess sisters, Autumnfair, Springfair, and Summerfair. All would have been happy and prosperous, had the curious sisters not opened the one door forbidden to them. The three evil dragons, now freed, immediately captured the princesses, killed the princes, overthrew the King, and imprisoned the Queen. The Queen bore two sons, who disappeared; while pregnant with a third child, she escaped—in the form of a white mare. Understanding his birthright and his purpose, Treeshaker sets out to reunite with his long-lost brothers—Stonecrumbler and Irontemperer—and with them, journey into the Underworld in order to defeat the dragons, reclaim their brides, and restore their kingdom.

The plot of White Mare is based on the 1862 Hungarian folktale Fehérlófia, by László Arany, with director Marcell Jankovics giving at the beginning a dedication to “the Scythians, Huns, Avars, and other nomadic peoples.” Though Jankovics had wanted to make a fairytale movie from the start, his original vision couldn’t be realized due to the political tensions prevalent in the Cold War Eastern Europe in which he grew up. According to animation historian Charles Solomon in the Blu-ray’s booklet:

“A scholar of mythology and symbolism, [Jankovics] initially planned to meld several folktales into a feature that would explore the cycles of time and space. [. . .] But according to Marxist theory, time is irreversible. A film that focused on the recurring cycles that characterize many myths could be perceived as anti-Marxist by the Soviet-dominated government.

Instead, Jankovics turned to ‘The Son of the White Mare,’ an oral epic of Central Asia that was brought to Europe by the early Hungarians. Like all folktales, it exists in multiple versions (more than 50 variations have been collected by scholars in the Carpathian Basin), and the filmmaker drew elements from a half-dozen accounts of the story.”

For unknown reasons, the film wasn’t distributed in America upon release. Very strange, not to mention downright devastating, considering the factors that would have worked in its favor:

- Jankovics had already proven himself an animation pioneer beforehand, having directed the very first Hungarian animated feature film, János Vitéz (Johnny Corncob) in 1973, and following with the Oscar-nominated short Sisyphus in 1974;

- Disney was in the middle of its Bronze Era, struggling due to its namesake’s passing in 1966;

- Aside from the syndication of Astro Boy, anime hadn’t yet made its mark in the west;

- Very few other western animated feature films made prior were remotely comparable to it, some exceptions including Fantasia, Fantastic Planet, and Yellow Submarine.

Still, White Mare did find success, being placed at #49 on the Olympiad of Animation in 1984 and premiering at the Los Angeles International Animation Celebration in 1985. Then, in 2019, LA studio Arbelos Films and the Hungarian Film Institute gave the movie a stunning 4K restoration, screening it at the 2019 Fantasia International Film Festival and planning a long-overdue theatrical release in the U.S. soon after. This plan was unfortunately shelved in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, so White Mare was instead made available to stream in America through Vimeo in late 2020, and then released on Blu-ray in 2021.

The “brave hero rescues damsel in distress from evil monsters” plot is pretty basic and antiquated on paper, but Jankovics makes it stand out by giving it a phantasmagoric 20th century coat of paint in every sense of the term. White Mare’s production and design was heavily influenced by the psychedelic drug culture of the 60’s, resulting in a piece meant to stun the senses and mystify the mind as well as entertain the eyes.

The music alone speak volumes (pun intended) of the alien world viewers are about to enter. Though the electronic soundtrack may seem better suited for equally surreal but more contemporarily-based movies like Labyrinth, Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, or 2001: A Space Odyssey, the synthesized ambience fits the mythological setting: dreamy and nightmarish all at once, completely transcendent of time, space, and all things mortal.

I think where Jankovics is at his most creative and clever is how he reimagines and enhances the story’s traditional fairytale tropes and symbols with his own unique artistic nuances, namely, his highly abstract design and heavy emphasis on vivid colors and symmetrical shapes. This is best portrayed by the three brothers, who are kind of like the incarnation of the Goldilocks concept of “too hot, too cold, just right”:

STONECRUMBER: [Nervously] Your Royal Highness, dear father . . . We were, uh, thinking . . .

IRONTEMPERER: [Rudely] Give us our fair share!

TREESHAKER: [Respectfully] Dear father and mother, our King and Queen. We would like to get married.

As is so with their polar opposite brides, and their adversaries, who, by the way, are not dragons in the traditional sense (I think of them more like golems myself, but that’s just me).

Stonecrumbler, the first-born, is colored in shades of coppery red with lots of teardrop-shaped curves (some more flattering than others). Such a design I believe fits his personality as a careless, hotheaded bumbler, slow in words and wit, with more rocks in his head than in his hands. These traits contrast the vein and sensual nature of his lusty, and dare I say, busty, destined bride, Autumnfair, while paralleling the Three-Headed Dragon, a crude, boorish oaf made of stone:

STONECRUMBLER: [Trembling after being pulled back up from the pit of the Underworld] There are so many nasty creatures down there, they almost pecked out my eyes. It was so dark, I couldn’t see my own hands.

--

AUTUMNFAIR: [Seductively to Treeshaker] What brought you here? No soul ever comes here.

TREESHAKER: [Awkwardly as she embraces him] I am here . . . I’ve come for you.

AUTUMNFAIR: [Suddenly pushes him away in disgust with a sneer] Oh just get lost, before my husband comes home. My husband is the three-headed dragon. And when he gets home, he’ll kill you.

--

THREE-HEADED DRAGON: Woman! I smell a stranger here. [. . .] Well then, let’s fight on the copper field!

Irontemperer, the middle brother, is a bit more competent than Stonecrumbler, though not by much. His triangular, silvery blue form represents an arrogance as cold and hard as the metal he molds like clay. His brashness is balanced out by his very needy and very whiny betrothed, Springfair; and her captor, the Seven-Headed Dragon, matches his aggression via the personification of war: a fully armed tank. (No, I’m not making that up):

IRONTEMPERER: [to Treeshaker as he finishes his sculpting his metal club] I will go with you, my friend. But first I want to know who is the strongest among us. [Increasingly aggressive] Who is going to lead us? Let’s wrestle!

--

SPRINGFAIR: [Terrified almost out of her wits] What brought you here? No soul ever comes here!

TREESHAKER: [Perfectly calm] I’ve come for you.

SPRINGFAIR: [Pushes him away, frantic] Oh just get lost, before my husband comes home. My husband is the seven-headed dragon. He can throw his club from seven miles. And when he gets home . . .

TREESHAKER: [Almost amused] . . . he’ll kill me, I know.

SPRINGFAIR: [Quiet now, but still fearful] Yes, he’ll kill you, right away.

--

SEVEN-HEADED DRAGON: Who’s here? I’ll tear him apart! [. . .] [To Treeshaker] You dog! You must die! My silver field is waiting for you.

And then there is Treeshaker, the youngest, and therefore, the kindest, bravest, and overall best, as is visually apparent from his hues of golden yellow and the sunlike spheres adorning his face. Some of his attractiveness is more subtle: his name and special ability symbolizing nature and life, as opposed to his brothers’ inorganic mineral names, and well as his modesty, as Stonecrumbler goes shirtless and Irontemperer’s smock covers only his front. Likewise, Treeshaker’s beloved, Summerfair, is more reserved and dignified than her sisters; and his enemy, the Twelve-headed Dragon, though his pixilated skyscraper form makes him look like a boss from a vintage Atari game, is nevertheless more terrifying and powerful than his brothers because of his intelligence and foresight:

TREESHAKER: [To his brothers] My dear brothers, my mother told me that the fairy princesses have been kidnapped by dragons. We must find the hole the dragons used to enter the Underworld. [. . .] [Addressing the golden castle] Castle, stop spinning! Or else, I’ll destroy you!

--

SUMMERFAIR: [With demure curiosity] What brought you here? No soul ever comes here.

TREESHAKER: [With true love] I’ve come for you.

SUMMERFAIR: [Embraces him] Oh, my sweet savior.

--

TWELVE-HEADED DRAGON: [With a booming malevolence] I know you, Treeshaker, Son of the White Mare. I’ve known ever since you were just a tiny fetus in your mother’s womb, that someday we would do battle. [. . .] You have killed two of my brothers. Even if you have a thousand lives, you’ll die for this. [. . .] Let’s see, then, how strong you are. Join me on the golden field.

Yet in spite of these obvious differences, I love the artistic touches which illustrate the warriors’ brotherly bond. Many shots cut or dissolve from one brother to another in such a way as to give the illusion that they are morphing into one another, while others show the circular ground rotating beneath them as they walk, as if their godly motion is what moves their entire world. And in one of the film’s most beautiful sequences, before beginning their journey, the trio swears their undying loyalty to each other by grasping hands around Irontemperer’s triangular club. Their linked arms dissolve into a flowing braid-like design as it rotates clockwise; the sides of the club multiply, changing it into a twelve-pointed sun, which in turn transforms into the brothers’ divine faces.

It’s movies like this that make both foreign animation and film as an art form so enthralling to me, not to mention remind me of the majesty and real-world significance of folklore. Jankovics not only turns what would otherwise be a very basic and clichéd story into a kaleidoscopic powerhouse of epic fantasy, but does so without diminishing its universal qualities or disparaging its noble heritage. I hope that many more hidden cinematic gems are found and polished so they may be given the admiration this cosmic jewel was once so sadly denied.

CREDITS:

All images, audio, and links belong to their respective owners; no copyright infringement is intended.

MAIN THEME:

“The Call” - Briand Morrison and Roxann Berglund

EPISODE SONG:

“The Human God” - Sean Zarn

“The Human God” - Sean Zarn

All other music and sound clips are from Son of the White Mare (directed by Marcell Jankovics; production by PannóniaFilm; distributed by MOKEP and Arbelos Films.)

Download the full 15-minute episode here!

Son of the White Mare on Wikipedia

Son of the White Mare on Arbelos' Official Website

Son of the White Mare on IMDb

Son of the White Mare on Rotten Tomatoes

Son of the White Mare on Metacritic

Son of the White Mare on Tv Tropes

Watch Son of the White Mare on Vimeo

Buy Son of the White Mare on Amazon

Buy Son of the White Mare on Ebay

^^ Back to Movies, Short Films, and Other Works of Cinema

Download the full 15-minute episode here!

Son of the White Mare on Wikipedia

Son of the White Mare on Arbelos' Official Website

Son of the White Mare on IMDb

Son of the White Mare on Rotten Tomatoes

Son of the White Mare on Metacritic

Son of the White Mare on Tv Tropes

Watch Son of the White Mare on Vimeo

Buy Son of the White Mare on Amazon

Buy Son of the White Mare on Ebay

^^ Back to Movies, Short Films, and Other Works of Cinema