The Triplets of Belleville

(2003, Rated PG-13)

5/6/22

The first day of my Children’s Media class at LSC is one that I won’t soon forget. Upon receiving my syllabus, I had to blink a few times at a particular book on my list: Carrie by Stephen King. “Is this for real?” I wondered. My classmates’ expressions told me they were having similar thoughts. Amused at our collective confusion, our professor simply said, “I know what you’re all thinking, and I promise it will make sense.” Turns out, he was right. Instead of focusing on the horror, try reading Carrie with classic fairy tales and their common tropes and symbols in mind, particularly Cinderella. You’ll be amazed, trust me. One of the most prominent questions our professor had us consider throughout the course was, “What makes a story for children?” If you’ve seen “kids’ movies” like Labyrinth and Watership Down as I had to in class, you’ll understand what a conundrum this actually was. This movie was no easier to categorize; the cover art alone makes the 1976 Carrie movie look like a real fairy tale (albeit a very dark one).

Madame Souza spends her days in a little house in the French countryside raising her orphaned grandson, Champion, who has an insatiable passion for cycling. Ever the devoted grandmother, she takes it upon herself to be his coach and train him for the prestigious Tour de France. During the great bike race, however, Champion is kidnapped by black clad mafia henchman to be a pawn in their underground gambling ring. Souza pursues them all the way across the Atlantic, only to lose them in the bustling city of Belleville. Fortunately, some improv percussion on a busted bike wheel attracts the attention and aid of Rose, Violette, and Blanche, three singing, swinging sisters known in the music hall world as the Triplets of Belleville. With the Triplets’ flair and street smarts, and her stubbornness and obese family dog, Bruno, on her side, Souza determines to take on as many mini mob bosses and giant gun-toting goons as necessary in order to rescue Champion.

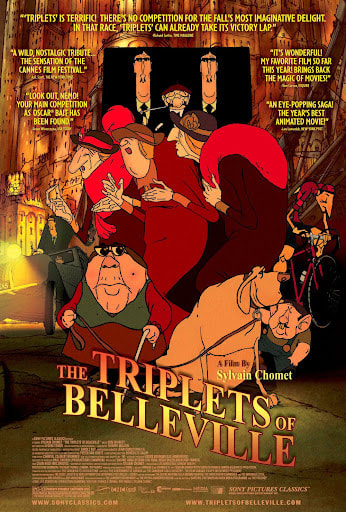

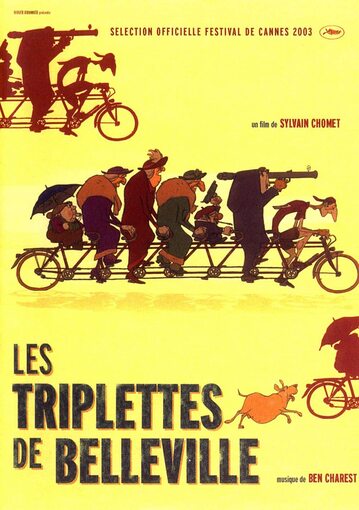

In the American theatrical trailer, A.O. Scott of the New York Times calls Sylvain Chomet’s film “[a] far cry from either Walt Disney or Japanese anime”. He couldn’t be more right, for many reasons. The Triplets of Belleville has the honor of being the first PG-13 film to receive an Academy Award nomination for Best Animated Feature. It lost (surprise, surprise . . .). Still, how could it not stick out like a sore thumb against more conventional fare like Finding Nemo and Brother Bear? And “sore” may very well be an apt word for this. Here are some of the most grotesque character designs I’ve ever seen—and I for one couldn’t be more fascinated. From gargantuan girths and scraggly limbs to bulging teeth and flabby skin, virtually every figure and feature has been deliberately and immensely exaggerated to be humorous and discomforting in equal measure. There is a 1513 painting by Flemish artist Quentin Matsys called “The Ugly Duchess”, said to have inspired John Tenniel’s original illustration of the Duchess in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. It shows an old woman in exquisite attire but who herself is wrinkled, square-jawed and has withered breasts, a sort of parody of traditional feminine beauty. That more or less sums up the unlikely heroines in this Wonderland of caricatures. No pretty Disney princesses or sexy anime warriors here! Madame Souza is as short and stout as a teapot, with thick glasses that magnify her irises to comical proportions and a single platform boot for an apparent leg length discrepancy. And then there are the Triplets: tall in height but stooped in back, their wizened faces sagging so heavily it looks like it takes effort just to move their features.

But what they may lack in aesthetic appearance, they make up for with their pluck and charm. This is actually crucial since the film contains virtually no spoken dialogue, the story told instead through pantomime, a type of stage theater in which the performers express meaning through gestures and songs. I find this artistic choice appropriate considering it can also refer to a ridiculous or confusing situation, an apt description for this movie’s vibe, more on that later. What few lines do exist (TV, radio, etc.) are for setting and atmosphere rather than plot (a plus for viewers who may dislike foreign films because of distracting subtitles). Souza herself speaks a grand total of twice, and never on screen, but no more than that is needed to show her sweet side: when she tries to bond with Champion as a child while watching TV, and then when she innocently but spectacularly fails to entertain her musical hostesses on their piano. But through her silence she exudes the kind of doggedness only a little old lady can pull off, whether she is habitually shoving her glasses up on her face with a firm finger before every important task or keeping incessant pace with her coach whistle during every cycling trip. The Triplets are just as delightful to watch and to hear, three 1930’s jazz counterparts to the Sister Act nuns. Their voices may be cracked and dusty and their glory days on the stage long gone, but their expert musical ears, boundless vigor, and upbeat attitudes keep them forever young and forever endearing.

All that said, Souza and the Triplets are a lot more human than the rest of the cast, in every sense of the word. Champion is like a strange hybrid of man and racehorse, with huge docile eyes, a stretched nose, bulging leg muscles, footsteps that clip-clop like hooves, and seemingly limitless stamina that gives new meaning to the term horsepower. But he is also broken in like a horse, putting up no fight whatsoever against any “handlers” and instead tamely following wherever he’s led with soft nickers and whinnies.

The bad guys make almost no sound at all, I think partly to make them intimidating, but mostly, with their design, I think for them to do so might make them even weirder. The animators take the stereotype of ten-foot-tall subordinates serving a less-than-one-foot-tall boss a comedic step further by building the former like the unnaturally rectangular monoliths from 2001: A Space Odyssey, and the thick-mustached, bulbous-nosed superior like the Mario Bros.’ drunk, narcoleptic uncle, his head sleepily flopped on every flat surface in front of him. Though, like Champion, the mafia’s tiny mechanic has some animal in him, too; in this case, a mouse, possessing large, round ears and buckteeth, and expressing himself through nothing but cute little squeaks.

Complimenting the bizarre visual style is the classic Looney Tunes sense of humor, which I think is just as smart. Take Belleville itself for an example. A combination of the world’s most prominent cities--Paris, New York City, Montreal, and Quebec—Belleville is a satire of extreme consumerism, with morbid obesity rampant among not only the background characters, but even certain inanimate icons, like the very well-fed Statue of Liberty—holding an ice cream cone and a cheeseburger on a plate instead of a torch and tabula ansata—and the much stockier Oscar statuettes lining the Triplets’ shelves. And remember how Looney Tunes would often lampoon mid-20th century celebrities like Humphrey Bogart, Frank Sinatra, and Jimmy Durante? Well, the opening sequence does just that. While the Triplets in their younger days perform on an old variety show, we see some rather risqué Fleischer-esque parodies of Romani-French jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt; black French entertainer Josephine Baker; and American dancer Fred Astaire. Although, the film’s grungier palette and comparative realism tends to make such humor more objectively insane. One of my favorite scenes of this kind is when Blanche treks to a pond, tosses a live shaft grenade into the water, and cheerfully waits under her umbrella for the exploding geyser to send a rain of dead frogs plopping into her fishing net for her to take to her sisters to cook for dinner.

And I don’t know whether or not this was intentional, but I also like how the filmmakers don’t just play with certain stereotypes, but mold and squash and tease them until they are as hilariously odd as the heroines. Besides the Triplets, being French, eating literally nothing but frogs (hence the extreme hunting method), they also make clever use of household items traditionally associated with stay-at-home women. During the climax, Rose’s frying pan makes a great weapon for bashing baddies unconscious and shielding against flying bullets. But perhaps the best example is the restaurant scene in which the Triplets perform a very unique musical number with a newspaper, a refrigerator’s steel rungs, and an old vacuum cleaner, the last of which the animators, according to the DVD commentary, had affectionately named “Mouf-Mouf.”

Fantasy Horror writer Clive Barker once said regarding pantomime:

“[In] truth there is much in the form I admire. Its artlessness for one; its riotous indifference to any rules of drama but its own; its guileless desire to delight. And of course beneath all its tarnish ways there is buried a story of primal simplicity: good against evil, love triumphing over hate and envy” (The Painter, the Creature and the Father of Lies, Pg. 246).

A perfectly ironic, yet ironically perfect description of this movie. At its core, The Triplets of Belleville is a familial search-and-rescue story, and the creators could have stopped at the already funny twist of the old grandmother saving the young adult grandson rather than vice versa. But the sheer absurdity of its characters, its eccentric soundtrack, and tongue-in-cheek wit turn a potentially dull and off-putting presentation into a joyride as exceptional as it is farcical.

CREDITS:

All images, audio, and links belong to their respective owners; no copyright infringement is intended.

MAIN THEME:

“The Call” – Briand Morrison and Roxann Berglund

Madame Souza spends her days in a little house in the French countryside raising her orphaned grandson, Champion, who has an insatiable passion for cycling. Ever the devoted grandmother, she takes it upon herself to be his coach and train him for the prestigious Tour de France. During the great bike race, however, Champion is kidnapped by black clad mafia henchman to be a pawn in their underground gambling ring. Souza pursues them all the way across the Atlantic, only to lose them in the bustling city of Belleville. Fortunately, some improv percussion on a busted bike wheel attracts the attention and aid of Rose, Violette, and Blanche, three singing, swinging sisters known in the music hall world as the Triplets of Belleville. With the Triplets’ flair and street smarts, and her stubbornness and obese family dog, Bruno, on her side, Souza determines to take on as many mini mob bosses and giant gun-toting goons as necessary in order to rescue Champion.

In the American theatrical trailer, A.O. Scott of the New York Times calls Sylvain Chomet’s film “[a] far cry from either Walt Disney or Japanese anime”. He couldn’t be more right, for many reasons. The Triplets of Belleville has the honor of being the first PG-13 film to receive an Academy Award nomination for Best Animated Feature. It lost (surprise, surprise . . .). Still, how could it not stick out like a sore thumb against more conventional fare like Finding Nemo and Brother Bear? And “sore” may very well be an apt word for this. Here are some of the most grotesque character designs I’ve ever seen—and I for one couldn’t be more fascinated. From gargantuan girths and scraggly limbs to bulging teeth and flabby skin, virtually every figure and feature has been deliberately and immensely exaggerated to be humorous and discomforting in equal measure. There is a 1513 painting by Flemish artist Quentin Matsys called “The Ugly Duchess”, said to have inspired John Tenniel’s original illustration of the Duchess in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. It shows an old woman in exquisite attire but who herself is wrinkled, square-jawed and has withered breasts, a sort of parody of traditional feminine beauty. That more or less sums up the unlikely heroines in this Wonderland of caricatures. No pretty Disney princesses or sexy anime warriors here! Madame Souza is as short and stout as a teapot, with thick glasses that magnify her irises to comical proportions and a single platform boot for an apparent leg length discrepancy. And then there are the Triplets: tall in height but stooped in back, their wizened faces sagging so heavily it looks like it takes effort just to move their features.

But what they may lack in aesthetic appearance, they make up for with their pluck and charm. This is actually crucial since the film contains virtually no spoken dialogue, the story told instead through pantomime, a type of stage theater in which the performers express meaning through gestures and songs. I find this artistic choice appropriate considering it can also refer to a ridiculous or confusing situation, an apt description for this movie’s vibe, more on that later. What few lines do exist (TV, radio, etc.) are for setting and atmosphere rather than plot (a plus for viewers who may dislike foreign films because of distracting subtitles). Souza herself speaks a grand total of twice, and never on screen, but no more than that is needed to show her sweet side: when she tries to bond with Champion as a child while watching TV, and then when she innocently but spectacularly fails to entertain her musical hostesses on their piano. But through her silence she exudes the kind of doggedness only a little old lady can pull off, whether she is habitually shoving her glasses up on her face with a firm finger before every important task or keeping incessant pace with her coach whistle during every cycling trip. The Triplets are just as delightful to watch and to hear, three 1930’s jazz counterparts to the Sister Act nuns. Their voices may be cracked and dusty and their glory days on the stage long gone, but their expert musical ears, boundless vigor, and upbeat attitudes keep them forever young and forever endearing.

All that said, Souza and the Triplets are a lot more human than the rest of the cast, in every sense of the word. Champion is like a strange hybrid of man and racehorse, with huge docile eyes, a stretched nose, bulging leg muscles, footsteps that clip-clop like hooves, and seemingly limitless stamina that gives new meaning to the term horsepower. But he is also broken in like a horse, putting up no fight whatsoever against any “handlers” and instead tamely following wherever he’s led with soft nickers and whinnies.

The bad guys make almost no sound at all, I think partly to make them intimidating, but mostly, with their design, I think for them to do so might make them even weirder. The animators take the stereotype of ten-foot-tall subordinates serving a less-than-one-foot-tall boss a comedic step further by building the former like the unnaturally rectangular monoliths from 2001: A Space Odyssey, and the thick-mustached, bulbous-nosed superior like the Mario Bros.’ drunk, narcoleptic uncle, his head sleepily flopped on every flat surface in front of him. Though, like Champion, the mafia’s tiny mechanic has some animal in him, too; in this case, a mouse, possessing large, round ears and buckteeth, and expressing himself through nothing but cute little squeaks.

Complimenting the bizarre visual style is the classic Looney Tunes sense of humor, which I think is just as smart. Take Belleville itself for an example. A combination of the world’s most prominent cities--Paris, New York City, Montreal, and Quebec—Belleville is a satire of extreme consumerism, with morbid obesity rampant among not only the background characters, but even certain inanimate icons, like the very well-fed Statue of Liberty—holding an ice cream cone and a cheeseburger on a plate instead of a torch and tabula ansata—and the much stockier Oscar statuettes lining the Triplets’ shelves. And remember how Looney Tunes would often lampoon mid-20th century celebrities like Humphrey Bogart, Frank Sinatra, and Jimmy Durante? Well, the opening sequence does just that. While the Triplets in their younger days perform on an old variety show, we see some rather risqué Fleischer-esque parodies of Romani-French jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt; black French entertainer Josephine Baker; and American dancer Fred Astaire. Although, the film’s grungier palette and comparative realism tends to make such humor more objectively insane. One of my favorite scenes of this kind is when Blanche treks to a pond, tosses a live shaft grenade into the water, and cheerfully waits under her umbrella for the exploding geyser to send a rain of dead frogs plopping into her fishing net for her to take to her sisters to cook for dinner.

And I don’t know whether or not this was intentional, but I also like how the filmmakers don’t just play with certain stereotypes, but mold and squash and tease them until they are as hilariously odd as the heroines. Besides the Triplets, being French, eating literally nothing but frogs (hence the extreme hunting method), they also make clever use of household items traditionally associated with stay-at-home women. During the climax, Rose’s frying pan makes a great weapon for bashing baddies unconscious and shielding against flying bullets. But perhaps the best example is the restaurant scene in which the Triplets perform a very unique musical number with a newspaper, a refrigerator’s steel rungs, and an old vacuum cleaner, the last of which the animators, according to the DVD commentary, had affectionately named “Mouf-Mouf.”

Fantasy Horror writer Clive Barker once said regarding pantomime:

“[In] truth there is much in the form I admire. Its artlessness for one; its riotous indifference to any rules of drama but its own; its guileless desire to delight. And of course beneath all its tarnish ways there is buried a story of primal simplicity: good against evil, love triumphing over hate and envy” (The Painter, the Creature and the Father of Lies, Pg. 246).

A perfectly ironic, yet ironically perfect description of this movie. At its core, The Triplets of Belleville is a familial search-and-rescue story, and the creators could have stopped at the already funny twist of the old grandmother saving the young adult grandson rather than vice versa. But the sheer absurdity of its characters, its eccentric soundtrack, and tongue-in-cheek wit turn a potentially dull and off-putting presentation into a joyride as exceptional as it is farcical.

CREDITS:

All images, audio, and links belong to their respective owners; no copyright infringement is intended.

MAIN THEME:

“The Call” – Briand Morrison and Roxann Berglund

EPISODE SONG:

“Bercez-Vous Beacoup” - George Ellsworth

“Bercez-Vous Beacoup” - George Ellsworth

All other sound and music clips are from The Triplets of Belleville (directed by Sylvain Chomet; production by Les Armateurs, Champion, Vivi Film, France 3 Cinema, RGP France, BBC Bristol, and BBC Worldwide; distributed by Diaphana Films, Cinéart, Alliance Atlantis, and Tartan Films).

Download the full 15-minute episode here!

The Triplets of Belleville on Wikipedia

Sylvain Chomet on Wikipedia

The Triplets of Belleville on IMDb

The Triplets of Belleville on Rotten Tomatoes

The Triplets of Belleville on Metacritic

The Triplets of Belleville on Common Sense Media

The Triplets of Belleville on Tv Tropes

Buy The Triplets of Belleville on Amazon

Buy The Triplets of Belleville at Barnes & Noble

Buy The Triplets of Belleville on Ebay

^^ Back to Movies, Short Films, and Other Works of Cinema

Download the full 15-minute episode here!

The Triplets of Belleville on Wikipedia

Sylvain Chomet on Wikipedia

The Triplets of Belleville on IMDb

The Triplets of Belleville on Rotten Tomatoes

The Triplets of Belleville on Metacritic

The Triplets of Belleville on Common Sense Media

The Triplets of Belleville on Tv Tropes

Buy The Triplets of Belleville on Amazon

Buy The Triplets of Belleville at Barnes & Noble

Buy The Triplets of Belleville on Ebay

^^ Back to Movies, Short Films, and Other Works of Cinema