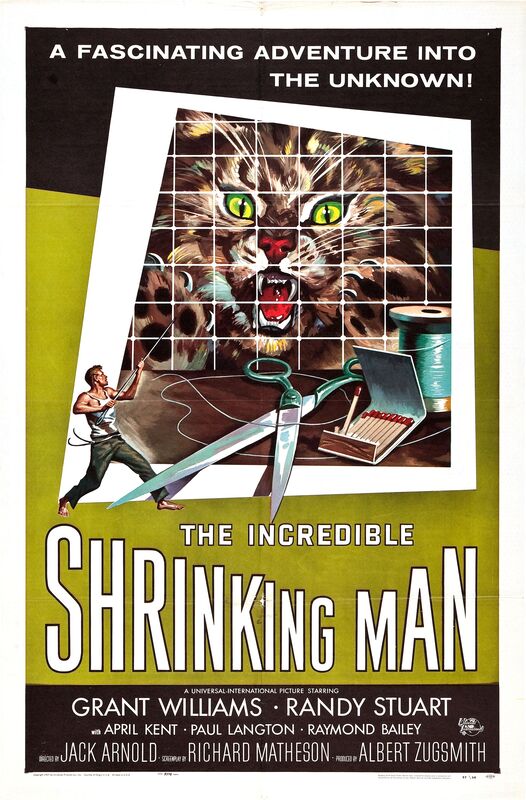

The Incredible Shrinking Man

(1956/1957, Ages 16 and Up)

1/7/22

Ever since I saw Walt Disney’s 1951 classic Alice in Wonderland as a child, I’ve been utterly fascinated by the idea of size alteration, a fairy-tale old concept that has persisted well into modern times. While giant monster flicks were huge (no pun intended) in the mid-20th century, abnormal shrinkage was also eagerly explored—and exploited—in cinema: Fantastic Voyage, Attack of the Puppet People, Dr. Cyclops, The Phantom Planet, the list goes on. However, for all these filmmakers’ albeit flimsy attempts to ground their plots in scientific reasoning and plausibility, this trope has generally been treated like either a grand adventure or a wacky dilemma, but little else. Be honest, would you willingly try to tame a spider the size of a bear?

Scott Carey is an ordinary 6 ft-tall man on vacation when he is suddenly enveloped in a mist that vanishes as quickly as it comes. Aside from a strange glittering on his skin, nothing appears to be amiss. Until his clothes begin to feel looser. And his wife, Louise, no longer has to stand on tiptoes in order to kiss him. And his wedding ring slips off his finger. Soon, the truth can’t be denied: Scott is shrinking. First comes frustration as doctors struggle in vain find a cure and his physical strength and social standing diminish with his size. Then humiliation as his lack of height labels him a freak in the eyes of his fellow man. Then rage as he becomes little more than a plaything at the mercy of towering giants. But these emotions pale against the terror of being mere inches tall. A run-in with a now monstrous animal traps him inside his cellar. And still he continues to shrink. Now a prisoner in the ever “expanding” depths of his own house, Scott’s daily fight for survival forces him to question his existence, his reality, and his very humanity as it threatens to disappear forever along with him.

Author Richard Matheson, also famous for What Dreams May Come, A Stir of Echoes, and I Am Legend, was inspired to write his book (originally called simply The Shrinking Man) by a scene from the 1953 comedy Let’s Do it Again, in which Gary accidentally puts Frank’s larger hat, and it sinks below his ears. This prompted Matheson to wonder: What if a man put on his own hat, and the same thing happened? While not as prolific, director Jack Arnold was a fine sci-fi master in his own right, best known, on top of Shrinking Man, for the classics It Came from Outer Space, Tarantula!, and, one of Universal Monster greats, Creature From the Black Lagoon.

One unique, if random, feature of the novel’s nonlinear structure: Within the seventeen chapters, pre-cellar flashbacks are sub-headed with Scott’s then height in inches, starting at “68”” in Chapter Two and ending at “7”” in Chapter Fifteen, when his entrapment is finally highlighted. The film, by contrast, presents the plot points in chronological order; not quite as interesting, but certainly easier to follow in the long run.

Being 1950’s science fiction, even an earthbound story wouldn’t be the same without something to call “alien.” Matheson combines chillingly vivid prose with epic fantasy imagery, and lead actor Grant Williams gives a somber and haunting narration over well-made oversized props and ambitious but solid visual effects, to turn ordinary living creatures into beasts of mythological proportions, and a common junk-filled cellar into a lonely, hostile world that this lone, tragic soul is condemned to traverse.

BOOK:

“The spider rushed at him across the shadowed sands, scrabbling wildly on its stalklike legs. Its body was a giant, glossy egg that trembled blackly as it charged across the windless mounds, its wake a score of sand-trickling scratches.

Paralysis locked the man. He saw the poisonous glitter of the spider eyes. He watched it scramble across a loglike stick, body mounted high on its motion-blurred legs, as high as the man’s shoulders.

Behind him, suddenly, the steel-encased flame flared into life with a thunder that shook the air. It jarred the man loose. With a sucking gasp, he spun around and ran, the damp sand crunching beneath his racing sandals.

[ . . . ]

The man dashed between the two giant cans that loomed like tanks above him. He threaded, racing, in between the silent bulks of all the clustered cans, past green and red and yellow sides all caked with livid smears.

[ . . . ]

The great orange mass loomed over the man now as he headed once more for the edge of the cliff. There was no time for hesitation. With an extra springing of his legs, he flung himself across the gulf and clutched with spastic fingers at the roughened ledge.

Wincing, he drew himself onto the splintered orange surface just as the spider reached the cliff’s edge. Jumping up, the man began running along the narrow ledge, not looking back. [ . . . ]

[ . . . ]

He limped slowly past the silent steel tower, which was an oil burner; past the huge red serpent, which was a nozzleless garden hose clumsily coiled on the floor, past the wide cushion whose case was covered with flower designs; past the immense orange structure, which was a stack of two wooden lawn chairs; past the great croquet mallets hanging in their racks. One of the wickets from the croquet set had been stuck in a groove on top of the lawn chair. It was what the man, in his flight, had grabbed for and missed. And the tanklike cans were used paint cans, and the spider was a black widow.

He lived in a cellar.” (Pg. 4-8)

FILM:

SCOTT: (Narrating; looking around the cellar with its gargantuan objects) The cellar floor stretched before me like some vast primeval plane, empty of life, littered with the relics of a vanished race. No desert-island castaway ever faced so bleak a prospect.

[ . . . ]

SCOTT: (Narrating; staring at the retreating spider he’s just fought off with a lance-sized pin) In my hunt for food, I had become the hunted. This time I survived. But I was no longer alone in my universe. (Turns and slumps against the wall of a matchbox) I had an enemy, the most terrifying ever beheld by human eyes.

Countless sci-fi stories of this era were created when fears of radiation and nuclear war were fresh in Americans’ minds, and Shrinking Man was no exception. But here, the sensational idea of shrinking is treated with surprisingly realistic, if Kafka-esque, care. Scott’s condition is described as a sort of “anti-cancer.” Yet just like traditional cancer, after the initial shock wears off, the practical implications inevitably rear their ugly heads. Scott’s worsening state means he can no longer be the breadwinner, leading to bills, bills and more bills. Fortunately (or not), there are plenty of healthy and insensitive parasites more than willing to milk such a fantastic sob story for all it’s worth, a fact Scott must make use of for his family’s sake, even as it erodes both his ego and his marriage.

BOOK:

“Days passed, one torture on another. Clothes were taken in for him, furniture got bigger, less manageable. Beth [their daughter] and Lou got bigger. Financial worries got bigger.

‘Scott, I hate to say it, but I don’t see how we can go on much longer on fifty dollars a week. With all of us to feed and clothe and house . . .’ Her voice trailed off; she shook her head in distress.

‘I suppose you expect me to go back to the paper.’

‘I didn’t say that. I merely said—’

‘I know what you said.’

‘Well, if it offends you, I’m sorry. Fifty dollars a week isn’t enough. What about when winter comes? What about winter clothes, and oil?’

He shook his head as if he were trying to shake away the need to think of it.

‘Do you think Marty would—’

‘I can’t ask Marty for more money,’ he said curtly.

‘Well . . .’ She said no more. She didn’t have to.

[ . . . ]

Then, the last week in July, Marty’s check didn’t come.

First they thought it was an oversight. But two more days went by and the check still didn’t come.

‘We can’t wait much longer, Scott,’ she said.

‘What about the savings account?’

‘There isn’t more than seventy dollars in it.’

‘Oh. Well . . . we’ll wait one more day,’ he said.

He spent that day in the living room, staring at the same page of the book he was supposedly reading.

He kept on telling himself he should go back to the Globe-Post, let them continue their series. Or accept one of the many offers for personal appearances. Or let those lurid magazines write his story. Or allow a ghost writer to grind out a book about his case. Then there would be enough money, then the insecurity that Lou feared so desperately would be ended.

But telling himself about it wasn’t enough. His revulsion against placing himself before the blatant curiosity of people was too strong.

He comforted himself. The check will come tomorrow, he kept repeating, it’ll come tomorrow.

But it didn’t. And that night they’d driven over to Marty’s and Marty had told him that he’d lost his contract with Fairchild and had to cut down operations to almost nothing. The checks would have to stop. He gave Scott a hundred dollars, but that was the end.” (Pg. 90-91)

FILM:

SCOTT: (Sitting in a now-oversized chair, his feet not touching the floor, dressed in boy’s clothes; glumly as he listens to Charlie’s suggestion to make reporters pay to run his story) All right. I’ll think about it. (Narrating) But really, was there any choice? We owed a great deal of money, and I had no job. There was no choice. None at all. And so, I became famous.

[ . . . ]

LOUISE: (Trying to comfort Scott, yet barely keeping together herself) Scott, people know. They-they realize, they’re not laughing at you.

SCOTT: They’re not?

LOUISE: No.

SCOTT: (Bitterly sarcastic) Why not? It’s funny, isn’t it? But it is. (Spreads his little arms out) See how funny I am? The child that looks like a man. Go on, laugh, Louise. Be like everyone else. It’s all right.

LOUISE: (Turns away, wretched and on the verge of tears)

SCOTT: (Getting angry) Well, why won’t you look at me? (Bangs his hands on the table in fury) Look at me!

But the best subversion of expectations comes from the shrinking itself. In most other stories, extreme size reductions clock in at minutes, if not seconds. But Scott shrinks a seventh of an inch per day; that’s one inch per week; roughly four inches per month; and so on. Think how much more excruciating it is to shrink that slowly, to know firsthand the condescending looks and remarks, and have all the time in the world to be haunted by memories of a once-normal past and fears of such an inconceivable future. What’s more, long before the mortal danger of smallness, Scott suffers a sort of social de-evolution according the 50s’ strict standards of masculinity. His weakness makes him “womanly”; his boy’s clothes make him “childlike”; and his increasingly tyrannical attitude makes him “inhuman.” This metaphor is brilliantly illustrated through Scott’s various horrible predicaments, most of which, unfortunately, aren’t in the film, which I think severely weakens it in this regard. But thankfully, the film does include Scott’s chance encounter with Clarice, a natural-born little person, who not only provides some much-needed intimacy and normalcy, however brief, but reminds him that, big or small, he is as human as anyone else.

BOOK:

“She looked back at him a long moment. Then, without a word, she stepped close to him and laid her cheek against his. She stood quietly as he put his arms around her.

‘Oh,’ he whispered, ‘Oh, God. To—’

She sobbed and pressed against him suddenly, her small hands catching at his back. Wordlessly they clung to each other in the quiet room, their tear-wet cheeks together.

‘My dear,’ she murmured, ‘my dear, my dear.’

He drew back his head and looked into her glistening eyes.

‘If you knew,’ he said brokenly. ‘If you—’

‘I do know,’ she said, running a trembling hand across his cheek.

‘Yes. Of course you do.’

He leaned forward and felt her warm lips change under his from soft acceptance to a harsh, demanding hunger.

He held her tensely. ‘Oh, God, to be a man again,’ he whispered. ‘Just to be a man again. To hold you like this.’

‘Yes. Do hold me. It’s been so long.’ After a few minutes, Clarice led him to the couch and they sat there holding tightly to each other’s hands, smiling at each other.” (Pg. 148)

[ . . . ]

“Yes, he was still a man. Two-sevenths of an inch tall and still a man.

He remembered the night he’d been with Clarice, and how, then too, it had come to him that he was still a man.

‘You aren’t pitiful,’ she whispered to him. ‘You’re a man.’ She’d dragged tense fingers across his chest.

It had been a moment of decisive alteration.

[ . . . ]

[ . . . ] A man’s self-estimation was, in the end, a matter of relativity.

[ . . . ]

And he saw that size had changed nothing essential; he still had his mind, he was still unique.” (Pg. 156-7)

FILM:

SCOTT: (A touch of desperation in his voice) How do you live with it, Miss Bruce? What do you do?

CLARICE: (With a slight shrug) I was born a midget. It’s the way I grew up. I know what’s happened to you and, well, that’s different.

SCOTT: Different. That’s another way of saying “alone,” isn’t it?

CLARICE: (Sympathetically) Oh, but you’re not alone now.

[ . . . ]

CLARICE: Oh, Scott, for people like you and me, the world can be a wonderful place. The sky is as blue as it is for the giants, the friends are as warm.

SCOTT: (Sadly) I wish I could believe that.

CLARICE: (Resolutely) You’ve got to believe that, don’t you?

SCOTT: (Tentatively) Yeah. Give me time, Clarice. I’ll learn.

Vintage sci-fi-fantasy/horror stories, while entertaining for reasons both good and bad, so often lack real, raw suspense and philosophical depth. The Incredible Shrinking Man may be as far-fetched in concept as aliens and giant monsters, but it is also much more pragmatic in presentation, and therefore much more psychologically devastating in execution, making it a rare and rewarding exception to the rules of its campier contemporaries. Though not my personal definition of nightmare fuel, I can say that since experiencing this story, I have never looked at basements, or of course, spiders, in quite the same way as before.

CREDITS:

All images, audio, and links belong to their respective owners; no copyright infringement is intended.

MAIN THEME:

“The Call” – Briand Morrison and Roxann Berglund

Scott Carey is an ordinary 6 ft-tall man on vacation when he is suddenly enveloped in a mist that vanishes as quickly as it comes. Aside from a strange glittering on his skin, nothing appears to be amiss. Until his clothes begin to feel looser. And his wife, Louise, no longer has to stand on tiptoes in order to kiss him. And his wedding ring slips off his finger. Soon, the truth can’t be denied: Scott is shrinking. First comes frustration as doctors struggle in vain find a cure and his physical strength and social standing diminish with his size. Then humiliation as his lack of height labels him a freak in the eyes of his fellow man. Then rage as he becomes little more than a plaything at the mercy of towering giants. But these emotions pale against the terror of being mere inches tall. A run-in with a now monstrous animal traps him inside his cellar. And still he continues to shrink. Now a prisoner in the ever “expanding” depths of his own house, Scott’s daily fight for survival forces him to question his existence, his reality, and his very humanity as it threatens to disappear forever along with him.

Author Richard Matheson, also famous for What Dreams May Come, A Stir of Echoes, and I Am Legend, was inspired to write his book (originally called simply The Shrinking Man) by a scene from the 1953 comedy Let’s Do it Again, in which Gary accidentally puts Frank’s larger hat, and it sinks below his ears. This prompted Matheson to wonder: What if a man put on his own hat, and the same thing happened? While not as prolific, director Jack Arnold was a fine sci-fi master in his own right, best known, on top of Shrinking Man, for the classics It Came from Outer Space, Tarantula!, and, one of Universal Monster greats, Creature From the Black Lagoon.

One unique, if random, feature of the novel’s nonlinear structure: Within the seventeen chapters, pre-cellar flashbacks are sub-headed with Scott’s then height in inches, starting at “68”” in Chapter Two and ending at “7”” in Chapter Fifteen, when his entrapment is finally highlighted. The film, by contrast, presents the plot points in chronological order; not quite as interesting, but certainly easier to follow in the long run.

Being 1950’s science fiction, even an earthbound story wouldn’t be the same without something to call “alien.” Matheson combines chillingly vivid prose with epic fantasy imagery, and lead actor Grant Williams gives a somber and haunting narration over well-made oversized props and ambitious but solid visual effects, to turn ordinary living creatures into beasts of mythological proportions, and a common junk-filled cellar into a lonely, hostile world that this lone, tragic soul is condemned to traverse.

BOOK:

“The spider rushed at him across the shadowed sands, scrabbling wildly on its stalklike legs. Its body was a giant, glossy egg that trembled blackly as it charged across the windless mounds, its wake a score of sand-trickling scratches.

Paralysis locked the man. He saw the poisonous glitter of the spider eyes. He watched it scramble across a loglike stick, body mounted high on its motion-blurred legs, as high as the man’s shoulders.

Behind him, suddenly, the steel-encased flame flared into life with a thunder that shook the air. It jarred the man loose. With a sucking gasp, he spun around and ran, the damp sand crunching beneath his racing sandals.

[ . . . ]

The man dashed between the two giant cans that loomed like tanks above him. He threaded, racing, in between the silent bulks of all the clustered cans, past green and red and yellow sides all caked with livid smears.

[ . . . ]

The great orange mass loomed over the man now as he headed once more for the edge of the cliff. There was no time for hesitation. With an extra springing of his legs, he flung himself across the gulf and clutched with spastic fingers at the roughened ledge.

Wincing, he drew himself onto the splintered orange surface just as the spider reached the cliff’s edge. Jumping up, the man began running along the narrow ledge, not looking back. [ . . . ]

[ . . . ]

He limped slowly past the silent steel tower, which was an oil burner; past the huge red serpent, which was a nozzleless garden hose clumsily coiled on the floor, past the wide cushion whose case was covered with flower designs; past the immense orange structure, which was a stack of two wooden lawn chairs; past the great croquet mallets hanging in their racks. One of the wickets from the croquet set had been stuck in a groove on top of the lawn chair. It was what the man, in his flight, had grabbed for and missed. And the tanklike cans were used paint cans, and the spider was a black widow.

He lived in a cellar.” (Pg. 4-8)

FILM:

SCOTT: (Narrating; looking around the cellar with its gargantuan objects) The cellar floor stretched before me like some vast primeval plane, empty of life, littered with the relics of a vanished race. No desert-island castaway ever faced so bleak a prospect.

[ . . . ]

SCOTT: (Narrating; staring at the retreating spider he’s just fought off with a lance-sized pin) In my hunt for food, I had become the hunted. This time I survived. But I was no longer alone in my universe. (Turns and slumps against the wall of a matchbox) I had an enemy, the most terrifying ever beheld by human eyes.

Countless sci-fi stories of this era were created when fears of radiation and nuclear war were fresh in Americans’ minds, and Shrinking Man was no exception. But here, the sensational idea of shrinking is treated with surprisingly realistic, if Kafka-esque, care. Scott’s condition is described as a sort of “anti-cancer.” Yet just like traditional cancer, after the initial shock wears off, the practical implications inevitably rear their ugly heads. Scott’s worsening state means he can no longer be the breadwinner, leading to bills, bills and more bills. Fortunately (or not), there are plenty of healthy and insensitive parasites more than willing to milk such a fantastic sob story for all it’s worth, a fact Scott must make use of for his family’s sake, even as it erodes both his ego and his marriage.

BOOK:

“Days passed, one torture on another. Clothes were taken in for him, furniture got bigger, less manageable. Beth [their daughter] and Lou got bigger. Financial worries got bigger.

‘Scott, I hate to say it, but I don’t see how we can go on much longer on fifty dollars a week. With all of us to feed and clothe and house . . .’ Her voice trailed off; she shook her head in distress.

‘I suppose you expect me to go back to the paper.’

‘I didn’t say that. I merely said—’

‘I know what you said.’

‘Well, if it offends you, I’m sorry. Fifty dollars a week isn’t enough. What about when winter comes? What about winter clothes, and oil?’

He shook his head as if he were trying to shake away the need to think of it.

‘Do you think Marty would—’

‘I can’t ask Marty for more money,’ he said curtly.

‘Well . . .’ She said no more. She didn’t have to.

[ . . . ]

Then, the last week in July, Marty’s check didn’t come.

First they thought it was an oversight. But two more days went by and the check still didn’t come.

‘We can’t wait much longer, Scott,’ she said.

‘What about the savings account?’

‘There isn’t more than seventy dollars in it.’

‘Oh. Well . . . we’ll wait one more day,’ he said.

He spent that day in the living room, staring at the same page of the book he was supposedly reading.

He kept on telling himself he should go back to the Globe-Post, let them continue their series. Or accept one of the many offers for personal appearances. Or let those lurid magazines write his story. Or allow a ghost writer to grind out a book about his case. Then there would be enough money, then the insecurity that Lou feared so desperately would be ended.

But telling himself about it wasn’t enough. His revulsion against placing himself before the blatant curiosity of people was too strong.

He comforted himself. The check will come tomorrow, he kept repeating, it’ll come tomorrow.

But it didn’t. And that night they’d driven over to Marty’s and Marty had told him that he’d lost his contract with Fairchild and had to cut down operations to almost nothing. The checks would have to stop. He gave Scott a hundred dollars, but that was the end.” (Pg. 90-91)

FILM:

SCOTT: (Sitting in a now-oversized chair, his feet not touching the floor, dressed in boy’s clothes; glumly as he listens to Charlie’s suggestion to make reporters pay to run his story) All right. I’ll think about it. (Narrating) But really, was there any choice? We owed a great deal of money, and I had no job. There was no choice. None at all. And so, I became famous.

[ . . . ]

LOUISE: (Trying to comfort Scott, yet barely keeping together herself) Scott, people know. They-they realize, they’re not laughing at you.

SCOTT: They’re not?

LOUISE: No.

SCOTT: (Bitterly sarcastic) Why not? It’s funny, isn’t it? But it is. (Spreads his little arms out) See how funny I am? The child that looks like a man. Go on, laugh, Louise. Be like everyone else. It’s all right.

LOUISE: (Turns away, wretched and on the verge of tears)

SCOTT: (Getting angry) Well, why won’t you look at me? (Bangs his hands on the table in fury) Look at me!

But the best subversion of expectations comes from the shrinking itself. In most other stories, extreme size reductions clock in at minutes, if not seconds. But Scott shrinks a seventh of an inch per day; that’s one inch per week; roughly four inches per month; and so on. Think how much more excruciating it is to shrink that slowly, to know firsthand the condescending looks and remarks, and have all the time in the world to be haunted by memories of a once-normal past and fears of such an inconceivable future. What’s more, long before the mortal danger of smallness, Scott suffers a sort of social de-evolution according the 50s’ strict standards of masculinity. His weakness makes him “womanly”; his boy’s clothes make him “childlike”; and his increasingly tyrannical attitude makes him “inhuman.” This metaphor is brilliantly illustrated through Scott’s various horrible predicaments, most of which, unfortunately, aren’t in the film, which I think severely weakens it in this regard. But thankfully, the film does include Scott’s chance encounter with Clarice, a natural-born little person, who not only provides some much-needed intimacy and normalcy, however brief, but reminds him that, big or small, he is as human as anyone else.

BOOK:

“She looked back at him a long moment. Then, without a word, she stepped close to him and laid her cheek against his. She stood quietly as he put his arms around her.

‘Oh,’ he whispered, ‘Oh, God. To—’

She sobbed and pressed against him suddenly, her small hands catching at his back. Wordlessly they clung to each other in the quiet room, their tear-wet cheeks together.

‘My dear,’ she murmured, ‘my dear, my dear.’

He drew back his head and looked into her glistening eyes.

‘If you knew,’ he said brokenly. ‘If you—’

‘I do know,’ she said, running a trembling hand across his cheek.

‘Yes. Of course you do.’

He leaned forward and felt her warm lips change under his from soft acceptance to a harsh, demanding hunger.

He held her tensely. ‘Oh, God, to be a man again,’ he whispered. ‘Just to be a man again. To hold you like this.’

‘Yes. Do hold me. It’s been so long.’ After a few minutes, Clarice led him to the couch and they sat there holding tightly to each other’s hands, smiling at each other.” (Pg. 148)

[ . . . ]

“Yes, he was still a man. Two-sevenths of an inch tall and still a man.

He remembered the night he’d been with Clarice, and how, then too, it had come to him that he was still a man.

‘You aren’t pitiful,’ she whispered to him. ‘You’re a man.’ She’d dragged tense fingers across his chest.

It had been a moment of decisive alteration.

[ . . . ]

[ . . . ] A man’s self-estimation was, in the end, a matter of relativity.

[ . . . ]

And he saw that size had changed nothing essential; he still had his mind, he was still unique.” (Pg. 156-7)

FILM:

SCOTT: (A touch of desperation in his voice) How do you live with it, Miss Bruce? What do you do?

CLARICE: (With a slight shrug) I was born a midget. It’s the way I grew up. I know what’s happened to you and, well, that’s different.

SCOTT: Different. That’s another way of saying “alone,” isn’t it?

CLARICE: (Sympathetically) Oh, but you’re not alone now.

[ . . . ]

CLARICE: Oh, Scott, for people like you and me, the world can be a wonderful place. The sky is as blue as it is for the giants, the friends are as warm.

SCOTT: (Sadly) I wish I could believe that.

CLARICE: (Resolutely) You’ve got to believe that, don’t you?

SCOTT: (Tentatively) Yeah. Give me time, Clarice. I’ll learn.

Vintage sci-fi-fantasy/horror stories, while entertaining for reasons both good and bad, so often lack real, raw suspense and philosophical depth. The Incredible Shrinking Man may be as far-fetched in concept as aliens and giant monsters, but it is also much more pragmatic in presentation, and therefore much more psychologically devastating in execution, making it a rare and rewarding exception to the rules of its campier contemporaries. Though not my personal definition of nightmare fuel, I can say that since experiencing this story, I have never looked at basements, or of course, spiders, in quite the same way as before.

CREDITS:

All images, audio, and links belong to their respective owners; no copyright infringement is intended.

MAIN THEME:

“The Call” – Briand Morrison and Roxann Berglund

EPISODE SONG:

“Internal Abyss” – Composed by Briand Morrison; Arranged by Erika Adams

“Internal Abyss” – Composed by Briand Morrison; Arranged by Erika Adams

All book excerpts are from The Incredible Shrinking Man by Richard Matheson (1994 Special Edition, published by Tor, a registered trademark of Tom Doherty Associates, LLC)

All other sound and music clips are from The Incredible Shrinking Man (directed by Jack Arnold; production by Universal-International Pictures Co., Inc.; distributed by Universal Pictures).

Download the full 15-minute episode here!

The Shrinking Man (novel) on Wikipedia

The Incredible Shrinking Man (film) on Wikipedia

Richard Matheson on Wikipedia

Jack Arnold on Wikipedia

The Shrinking Man (novel) on Goodreads

The Incredible Shrinking Man (film) on IMDb

The Incredible Shrinking Man (film) on Rotten Tomatoes

The Incredible Shrinking Man on Tv Tropes

The Incredible Shrinking Man (film) on Criterion

The Incredible Shrinking Man (film) on TMC

Buy The Shrinking Man (novel) on Amazon

Buy The Incredible Shrinking Man (film) on Amazon

Buy The Incredible Shrinking Man (novel & film) on Ebay

Buy Richard Matheson’s Unrealized Dreams (containing the complete script of the canceled film sequel, The Fantastic Little Girl)

^^ Back to Adaptations, Retellings, and Old Tales in New Light

All other sound and music clips are from The Incredible Shrinking Man (directed by Jack Arnold; production by Universal-International Pictures Co., Inc.; distributed by Universal Pictures).

Download the full 15-minute episode here!

The Shrinking Man (novel) on Wikipedia

The Incredible Shrinking Man (film) on Wikipedia

Richard Matheson on Wikipedia

Jack Arnold on Wikipedia

The Shrinking Man (novel) on Goodreads

The Incredible Shrinking Man (film) on IMDb

The Incredible Shrinking Man (film) on Rotten Tomatoes

The Incredible Shrinking Man on Tv Tropes

The Incredible Shrinking Man (film) on Criterion

The Incredible Shrinking Man (film) on TMC

Buy The Shrinking Man (novel) on Amazon

Buy The Incredible Shrinking Man (film) on Amazon

Buy The Incredible Shrinking Man (novel & film) on Ebay

Buy Richard Matheson’s Unrealized Dreams (containing the complete script of the canceled film sequel, The Fantastic Little Girl)

^^ Back to Adaptations, Retellings, and Old Tales in New Light