Lives of the Monster Dogs

(1997, Ages 17 and Up)

2/3/17

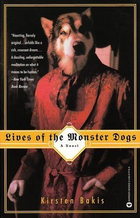

There is an annual book sale that takes place at the Duluth Public Library in the summer that I always enjoy attending at least once during the three to four days it runs. Even if I end up leaving empty-handed—and every so often I do if nothing sticks out at me—I’m still satisfied as I get a chance to reminisce about the titles that I remember from my youth while pondering on what’s come out that I may have missed. I was at one such sale a few years back when my eye fell upon this book tucked upon a shelf of Adult Fiction. After reading the title on the spine but before actually taking the book from the shelf, I wondered if it was some sort of metaphor. Something political, maybe, or relating to a war or scandal or some other piece of history that I’d likely never heard of. My curiosity piqued, I pulled out the book and my eyes widened: to my surprise, the cover art was quick to tell me that the book’s title was more than a bit literal. The picture showed what appeared to be a person in a wine-red silk shirt, but this person had the head of a beautiful dog; I didn’t know precisely what the breed was, but to me it looked like a Siberian Husky. Needless to say, the synopsis only further guaranteed my purchase.

The people of 2008 New York get the surprise of their lives when a group of refugees arrive in their city hoping to build a new life for themselves, having been completely isolated from the rest of the world for nearly a century. But these are no ordinary refugees; in fact, they’re not even human. They are a race of highly intelligent dogs created through years of scientific experimentation. Able to walk and speak as humans do, and attired in elegant gowns, tailcoats and top hats, they are the epitome of 19th century European wealth and nobility, and the fascinated New Yorkers welcome them with open arms. Though curious herself, struggling college student Cleo Pira is too focused on her own daily life to dwell too much on them. That is, until she is unexpectedly befriended by the dogs’ pensive historian, German Shepherd Ludwig von Sacher, and later commissioned to write news articles about their various plans and exploits. She accepts the offer as it not only pays well, but allows her to meet the other dogs and learn more about their personal lives. But then she learns the dogs’ most terrible secret of all: they are being afflicted one by one by an incurable Alzheimer’s-like disease that eats away at their humanity, reverting them more and more to their original canine state while slowly and painfully killing them. And when the dogs host an extravagant public party at the new castle built as both a new home for themselves and as a gift to New York, Cleo realizes that she may have no choice but to bear witness to the living nightmare of their seemingly inevitable extinction.

Excited though I was to read this book, a bit of suspicion nevertheless crept into my mind after the first few pages. I wondered if this was going to be a Beauty-and-the-Beast or Romeo-and-Juliet scenario, or a case of “good human protects good creatures from evil/ignorant humans”. As it turns out, neither were the case, which frankly was a nice change of pace. But in all seriousness, if something like this were to actually occur and everyone knew it for a fact, there would be utter chaos in some form or another. I think that was the aspect that surprised me most and where my suspension of disbelief was most tested because the apparent ease with which the humans accept the dogs seems questionable at best. At the same time, though, I’m glad to experience a story where one can explore the events and consequences of a hitherto impossible happening in the real-world of the 21st century without the anarchic side of human nature getting too much in the way.

Similarly to books like Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Stephen King’s Carrie, and Max Brooks’ World War Z, Lives of the Monster Dogs is in part an epistolary novel told through the letters, journal entries, and news articles written by the central characters. This adds an extra layer of melancholy realism to the narrative. As the tale progresses, there is the increasingly oppressive feeling that something is going to be lost forever when it is least expected, whether it be a self-indulgent novelty or something far more precious—and that is a line constantly blurred throughout.

In spite of all the praise and attention they receive, the dogs, especially Ludwig, hold no illusions as to how ridiculous they must appear to the humans. There is no explicit racism in the story, but it is still plain that the differences between Cleo and the dogs are too great not to create some tension between them. There is one scene in particular where Cleo joins Ludwig for lunch, and she can’t help but notice the awkward ways in which he tries to acclimate himself to human dining. A subtle discomfort lingers even after an amicable parting:

“Once when I passed [Ludwig] the bread, without thinking I set it down a few inches beyond the far edge of his plate, and I watched with fascination how he flipped his tail upward to hook it under one of the horizontal slats in the back of his chair, to keep himself from falling as he leaned over to get the silver wire basket.

‘You are laughing at me,’ he said.

‘No, I was just noticing how you used your tail . . .’

‘How could you do anything but laugh at me?’ He paused. ‘It’s all right.’

‘But I wasn’t.’

‘Of course you were. I can imagine what I look like to you. It’s awkward, and I don’t do a very good job. Your world wasn’t designed for dogs.’

‘I know.’

‘You don’t know.’

‘All right, I don’t know,’ I said. I could feel tears stinging somewhere in the upper part of my nose.

We ate the rest of the meal in silence. When we were finished, Ludwig looked up at me, folding his napkin in his hands. He seemed tired.

[. . .]

‘Listen, I didn’t mean to offend you,’ I said. ‘I’m sorry if I have.’

Ludwig closed his eyes for a second. ‘You haven’t.’

He pushed against the edge of the table to move his chair back a little, then lowered his feet to the ground one at a time, holding on to the edge of the table as he stood up. I got up, too.

‘I’ll see you to the door,’ he said.

At the door, leaning on his cane, he offered me his hand and held mine for a moment in his stiff mechanical grip.

‘Goodbye, Cleo. I hope I will be able to see you again,’ he said.

‘I’d like that a lot,’ I said. ‘I really would.’" (Pg. 72-73)

I believe that Bakis uses the very impossibility of the dogs to represent the misgiving that life itself may very well be not only pointless, but perhaps even the greatest cosmic joke ever conceived. This point of view also implants in the characters a sort of god-worshiping complex that is more than a bit unhealthy. As Ludwig fights to write down his people’s history before the disease takes him entirely, his mind always returns to Augustus Rank, the human scientist who created the monster dogs. Seeing Ludwig try in vain to capture even the smallest trace of his creator reminds me of how people struggle to get in touch with God, and from there make better sense of their otherwise pitiful, earthly existence, time and again without success:

“Augustus, you were wrong! Your dogs have forgotten you!

[. . .]

If only I could tell him, I think I could understand the history of my race—I could understand what he meant by creating us, what we are.

I do feel a kind of sympathy for him. I can see that he was lonely, and how much he wanted us. But I feel no real love for him, and that is what is needed to re-create him.

He was able to live his whole life sustained only by hope. But I am not so perfect. Like all of us, I grew tired of waiting and wanted to make a life for myself here and now. And now the pure, clear, focused desire for him is gone—I am no longer a dog waiting by the door with one single thought in its mind.

I can’t reconstruct that love, that hope. The past is disintegrating. I try once again to muster the feeling, and I can’t. I think my mind is wandering—it may be one of my memory lapses coming on. [. . .] How unlike Augustus Rank I am, who died with pure hope on his mind.

This is it. Just now a thin involuntary whine escaped my lips and I stopped typing to bury my nose once again among the papers on my desk, to take in the meaningless smells of Augustus, the soft burning reek of oxidizing paper, the flat scent of photocopies and the musty take of ferrotypes.

It is really hopeless—he does not exist anymore. [. . .] Since my glasses are off and I have ink stuck to my nose, my own senses are dulled, too, and I can’t perceive anything clearly; it seems to me that the whole world is decaying.” (Pg. 12-13)

[. . .]

“[. . .] I emerged from my memory lapse a few hours ago, and—I cannot describe my state of mind since then.

[. . .]

There were piles of feces in the corners of my apartment. I am half-starved—[. . .] The front door and the floor beneath it are ruined with scratch marks, and the fingertips of my prosthetic hands are now tangles of tiny frayed wires and torn rubber. [. . .] Several of my teeth are chipped, and my nose and tongue are bruised. Much of my furniture and all of my rugs [. . .] have been torn up and they are soaked with urine. [. . .]

When I emerged from this state at one o’clock and saw what I had done, I sat down and howled. [. . .] I am a dog. God help me. (Pg. 85-86)

There are some dogs, however, who would rather accept their death with grace and dignity—a fact that Cleo can hardly bear. In a dilemma not unlike the issue of assisted suicide, Cleo is torn between wanting to respect the dogs’ wishes to die as they see fit and begging them to keep fighting to live. But as this already bizarre reality she is now a part of descends into even deeper madness, she realizes she would nevertheless do anything to protect it. Some of these selfish feelings may come from a bit of celebrity obsession to an extent, but I also think that Cleo’s reflections illustrate people’s tendency to cling to anything that eases any pain or emptiness they may feel—and few desires are more human than that:

“Late that night I woke up with fur in my mouth, crying. My face was buried in Lydia’s deep mane, and it was dark. [. . .] She must have just curled up beside me when she’d come in. Now we lay together on the big velvet couch, and though it was warm and quiet and my cheek was pressed against Lydia’s comforting fur, I felt terrible. I couldn’t tell what I was crying about. [. . .] It wasn’t the hopelessness of all of the dogs’ situations, or the lost spirit of Rank [. . .] though that was part of it, too. I felt that I had wandered out beyond the edge of a circle of light where I’d always lived, onto an endless plain. [. . .]

Maybe all I was thinking that night while I looked up at the red cloudy sky, wrapped up in Lydia’s nightgown and crying, was that I wanted to be with the dogs, wherever they were going, even though I knew it was impossible. They weren’t even gone and already I missed them so much that my whole body ached. The raw pain of having joints and muscles and organs, the uncushioned feeling of living, without hope or love, my throbbing heart, it all hurt so much. I just didn’t want to be in the world without them.” (Pg. 265-266)

This story is not categorized within any one genre, but that just adds to its uniqueness, with characters almost worthy of a Shakespearian tragedy and a plot that blurs the line between affection and obsession. Lives of the Monster Dogs not only explores the sometimes eerie similarities between human and animal, but illustrates the agony that sentience can bring, and begs the question of how far one is willing to go for what they believe is love or to satisfy the longing for meaning in one’s life, something sought after by both man and beast.

CREDITS:

All images, audio, and links belong to their respective owners; no copyright infringement is intended.

All book excerpts are from Lives of the Monster Dogs by Kirsten Bakis (first edition, published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux).

MAIN THEME:

“The Call” – Briand Morrison and Roxann Berglund

The people of 2008 New York get the surprise of their lives when a group of refugees arrive in their city hoping to build a new life for themselves, having been completely isolated from the rest of the world for nearly a century. But these are no ordinary refugees; in fact, they’re not even human. They are a race of highly intelligent dogs created through years of scientific experimentation. Able to walk and speak as humans do, and attired in elegant gowns, tailcoats and top hats, they are the epitome of 19th century European wealth and nobility, and the fascinated New Yorkers welcome them with open arms. Though curious herself, struggling college student Cleo Pira is too focused on her own daily life to dwell too much on them. That is, until she is unexpectedly befriended by the dogs’ pensive historian, German Shepherd Ludwig von Sacher, and later commissioned to write news articles about their various plans and exploits. She accepts the offer as it not only pays well, but allows her to meet the other dogs and learn more about their personal lives. But then she learns the dogs’ most terrible secret of all: they are being afflicted one by one by an incurable Alzheimer’s-like disease that eats away at their humanity, reverting them more and more to their original canine state while slowly and painfully killing them. And when the dogs host an extravagant public party at the new castle built as both a new home for themselves and as a gift to New York, Cleo realizes that she may have no choice but to bear witness to the living nightmare of their seemingly inevitable extinction.

Excited though I was to read this book, a bit of suspicion nevertheless crept into my mind after the first few pages. I wondered if this was going to be a Beauty-and-the-Beast or Romeo-and-Juliet scenario, or a case of “good human protects good creatures from evil/ignorant humans”. As it turns out, neither were the case, which frankly was a nice change of pace. But in all seriousness, if something like this were to actually occur and everyone knew it for a fact, there would be utter chaos in some form or another. I think that was the aspect that surprised me most and where my suspension of disbelief was most tested because the apparent ease with which the humans accept the dogs seems questionable at best. At the same time, though, I’m glad to experience a story where one can explore the events and consequences of a hitherto impossible happening in the real-world of the 21st century without the anarchic side of human nature getting too much in the way.

Similarly to books like Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Stephen King’s Carrie, and Max Brooks’ World War Z, Lives of the Monster Dogs is in part an epistolary novel told through the letters, journal entries, and news articles written by the central characters. This adds an extra layer of melancholy realism to the narrative. As the tale progresses, there is the increasingly oppressive feeling that something is going to be lost forever when it is least expected, whether it be a self-indulgent novelty or something far more precious—and that is a line constantly blurred throughout.

In spite of all the praise and attention they receive, the dogs, especially Ludwig, hold no illusions as to how ridiculous they must appear to the humans. There is no explicit racism in the story, but it is still plain that the differences between Cleo and the dogs are too great not to create some tension between them. There is one scene in particular where Cleo joins Ludwig for lunch, and she can’t help but notice the awkward ways in which he tries to acclimate himself to human dining. A subtle discomfort lingers even after an amicable parting:

“Once when I passed [Ludwig] the bread, without thinking I set it down a few inches beyond the far edge of his plate, and I watched with fascination how he flipped his tail upward to hook it under one of the horizontal slats in the back of his chair, to keep himself from falling as he leaned over to get the silver wire basket.

‘You are laughing at me,’ he said.

‘No, I was just noticing how you used your tail . . .’

‘How could you do anything but laugh at me?’ He paused. ‘It’s all right.’

‘But I wasn’t.’

‘Of course you were. I can imagine what I look like to you. It’s awkward, and I don’t do a very good job. Your world wasn’t designed for dogs.’

‘I know.’

‘You don’t know.’

‘All right, I don’t know,’ I said. I could feel tears stinging somewhere in the upper part of my nose.

We ate the rest of the meal in silence. When we were finished, Ludwig looked up at me, folding his napkin in his hands. He seemed tired.

[. . .]

‘Listen, I didn’t mean to offend you,’ I said. ‘I’m sorry if I have.’

Ludwig closed his eyes for a second. ‘You haven’t.’

He pushed against the edge of the table to move his chair back a little, then lowered his feet to the ground one at a time, holding on to the edge of the table as he stood up. I got up, too.

‘I’ll see you to the door,’ he said.

At the door, leaning on his cane, he offered me his hand and held mine for a moment in his stiff mechanical grip.

‘Goodbye, Cleo. I hope I will be able to see you again,’ he said.

‘I’d like that a lot,’ I said. ‘I really would.’" (Pg. 72-73)

I believe that Bakis uses the very impossibility of the dogs to represent the misgiving that life itself may very well be not only pointless, but perhaps even the greatest cosmic joke ever conceived. This point of view also implants in the characters a sort of god-worshiping complex that is more than a bit unhealthy. As Ludwig fights to write down his people’s history before the disease takes him entirely, his mind always returns to Augustus Rank, the human scientist who created the monster dogs. Seeing Ludwig try in vain to capture even the smallest trace of his creator reminds me of how people struggle to get in touch with God, and from there make better sense of their otherwise pitiful, earthly existence, time and again without success:

“Augustus, you were wrong! Your dogs have forgotten you!

[. . .]

If only I could tell him, I think I could understand the history of my race—I could understand what he meant by creating us, what we are.

I do feel a kind of sympathy for him. I can see that he was lonely, and how much he wanted us. But I feel no real love for him, and that is what is needed to re-create him.

He was able to live his whole life sustained only by hope. But I am not so perfect. Like all of us, I grew tired of waiting and wanted to make a life for myself here and now. And now the pure, clear, focused desire for him is gone—I am no longer a dog waiting by the door with one single thought in its mind.

I can’t reconstruct that love, that hope. The past is disintegrating. I try once again to muster the feeling, and I can’t. I think my mind is wandering—it may be one of my memory lapses coming on. [. . .] How unlike Augustus Rank I am, who died with pure hope on his mind.

This is it. Just now a thin involuntary whine escaped my lips and I stopped typing to bury my nose once again among the papers on my desk, to take in the meaningless smells of Augustus, the soft burning reek of oxidizing paper, the flat scent of photocopies and the musty take of ferrotypes.

It is really hopeless—he does not exist anymore. [. . .] Since my glasses are off and I have ink stuck to my nose, my own senses are dulled, too, and I can’t perceive anything clearly; it seems to me that the whole world is decaying.” (Pg. 12-13)

[. . .]

“[. . .] I emerged from my memory lapse a few hours ago, and—I cannot describe my state of mind since then.

[. . .]

There were piles of feces in the corners of my apartment. I am half-starved—[. . .] The front door and the floor beneath it are ruined with scratch marks, and the fingertips of my prosthetic hands are now tangles of tiny frayed wires and torn rubber. [. . .] Several of my teeth are chipped, and my nose and tongue are bruised. Much of my furniture and all of my rugs [. . .] have been torn up and they are soaked with urine. [. . .]

When I emerged from this state at one o’clock and saw what I had done, I sat down and howled. [. . .] I am a dog. God help me. (Pg. 85-86)

There are some dogs, however, who would rather accept their death with grace and dignity—a fact that Cleo can hardly bear. In a dilemma not unlike the issue of assisted suicide, Cleo is torn between wanting to respect the dogs’ wishes to die as they see fit and begging them to keep fighting to live. But as this already bizarre reality she is now a part of descends into even deeper madness, she realizes she would nevertheless do anything to protect it. Some of these selfish feelings may come from a bit of celebrity obsession to an extent, but I also think that Cleo’s reflections illustrate people’s tendency to cling to anything that eases any pain or emptiness they may feel—and few desires are more human than that:

“Late that night I woke up with fur in my mouth, crying. My face was buried in Lydia’s deep mane, and it was dark. [. . .] She must have just curled up beside me when she’d come in. Now we lay together on the big velvet couch, and though it was warm and quiet and my cheek was pressed against Lydia’s comforting fur, I felt terrible. I couldn’t tell what I was crying about. [. . .] It wasn’t the hopelessness of all of the dogs’ situations, or the lost spirit of Rank [. . .] though that was part of it, too. I felt that I had wandered out beyond the edge of a circle of light where I’d always lived, onto an endless plain. [. . .]

Maybe all I was thinking that night while I looked up at the red cloudy sky, wrapped up in Lydia’s nightgown and crying, was that I wanted to be with the dogs, wherever they were going, even though I knew it was impossible. They weren’t even gone and already I missed them so much that my whole body ached. The raw pain of having joints and muscles and organs, the uncushioned feeling of living, without hope or love, my throbbing heart, it all hurt so much. I just didn’t want to be in the world without them.” (Pg. 265-266)

This story is not categorized within any one genre, but that just adds to its uniqueness, with characters almost worthy of a Shakespearian tragedy and a plot that blurs the line between affection and obsession. Lives of the Monster Dogs not only explores the sometimes eerie similarities between human and animal, but illustrates the agony that sentience can bring, and begs the question of how far one is willing to go for what they believe is love or to satisfy the longing for meaning in one’s life, something sought after by both man and beast.

CREDITS:

All images, audio, and links belong to their respective owners; no copyright infringement is intended.

All book excerpts are from Lives of the Monster Dogs by Kirsten Bakis (first edition, published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux).

MAIN THEME:

“The Call” – Briand Morrison and Roxann Berglund

EPISODE SONGS:

“Monster Fugue” - Briand Morrison and Roxann Berglund

“Monster Fugue” - Briand Morrison and Roxann Berglund

“Always on My Mind” - Briand Morrison and Roxann Berglund

“Deep of the Night" - Briand Morrison and Roxann Berglund

Download the full 15-minute episode here!

Lives of the Monster Dogs on Wikipedia

Kirsten Bakis on Wikipedia

Lives of the Monster Dogs on Goodreads

Buy Lives of the Monster Dogs on Amazon

Buy Lives of the Monster Dogs at Barnes & Noble

Buy Lives of the Monster Dogs on Ebay

^^ Back to Books, Graphic Novels, and Other Works of Literature

Lives of the Monster Dogs on Wikipedia

Kirsten Bakis on Wikipedia

Lives of the Monster Dogs on Goodreads

Buy Lives of the Monster Dogs on Amazon

Buy Lives of the Monster Dogs at Barnes & Noble

Buy Lives of the Monster Dogs on Ebay

^^ Back to Books, Graphic Novels, and Other Works of Literature