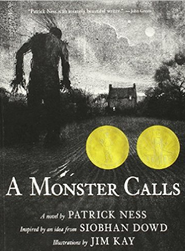

A Monster Calls

(2011, Ages 12 and Up)

8/21/15

It is very rare that a book moves me to tears, but when it does, it really does. Only four novels have ever had this sort of impact on me: Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist, from sheer joy; J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, from the pain of loss, for what are now probably obvious reasons; and Kate DiCamillo’s The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane, for a bit of both sadness and hope. The fourth I’m going to discuss here, for its evocative honesty in the midst of relentless anguish. It was not only the story that is so heart-rending, but the history of its creation.

A Monster Calls is the story of Conor, a 13-year-old boy living in present-day Britain. Ever since his mother was diagnosed with a terrible illness—implied to be cancer due to the descriptions of hair loss and the treatments that sap all her energy—Conor has been suffering from constant nightmares. Or rather, a single nightmare over and over again, involving a black creature with long tenticles glowing eyes that threaten to paralyze and suffocate him. One night, to Conor’s great surprise, he wakes up to find another kind of monster, this one very real and very different, seeming to be made up of branches that “[twist] around one another, always creaking, always groaning”, and “thin, needle-like leaves weaving together to make a green, furry skin that [moves] and [breathes] as there were muscles and lungs underneath” (p. 5). This monster claims to be the very spirit of the earth, most often taking the form of a yew tree. More to the point, it claims that it was summoned by Conor himself, yet the latter can’t recall such a thing. The reason for its coming, says the monster, is to heal Conor (from what Conor has no idea); but in order to do so, the monster must tell Conor three stories from its past travels across the lands of the world, after which Conor tell the monster a fourth in turn: the truth that he has been denying and that he would rather die than admit.

Though this novel was written by Chaos Walking trilogy author Patrick Ness, the idea for it was conceived by Siobhan Dowd, writing activist and author of four young adult novels. She was unfortunately diagnosed with severe terminal breast cancer and, passed away this day in 2007 at the age of 47 before she could further develop the idea. Ness was then contacted by Dowd’s Walker Books editor, Denise Johnstone-Burt (who had previously worked with both writers, though the two never met personally) to put Dowd’s story to paper. To this day, A Monster Calls is the only book whose creators have been awarded both the Carnegie and Kate Greenaway Medals, Ness for literature and Jim Kay for illustration, respectively.

It would be very easy for one seeing this book for the first time to believe it is a horror or suspense story; that’s what I believed at first, and not only because of the title. According to the biography at the back of the book, Kay “used everything from beetles to breadboards to create interesting marks and textures.” Indeed, many of the pictures have a very harsh, scratchy look to them, especially the monster with its thousands of dense clusters of branches and twigs, making it appear all the more wild and imposing, just like nature and the land it embodies and represents. The sky and other environments throughout often appear blotted or streaked, like either a terrible storm is brewing and just waiting to unleash its wrath, or the sky itself is as miserable as the characters in the story and just as unable or unwilling to shed its “tears.” In many scenes, Conor is often depicted as a white silhouette against almost complete blackness, whether it be the monster, his nightmare, or even sometimes the real world, symbolizing to me how the worst aspects of Connor’s reality continually threaten to overwhelm what parts of himself remain and swallow him up. No human faces are ever visually depicted, but on the rare occasion that eyes are shown, like those of the monster or some animal, they are always white with no pupils, either cold and unpredictable or dull and inert.

While this story certainly is frightening to an extent, it is less so in the sense of devilish horror than of pure despair. From Connor’s point of view, the reader gets the sense that he feels he’s the only one who has any faith that his mother will eventually recover, fueling the seemingly justified bitterness that Conor harbors within his heart. While he believes and wishes for his mother’s life more than anything, it is as though the rest of his family is simply giving up and moving on with their own lives while wanting Conor to “be brave” and “talk about what’s going to happen”.

His divorced father is remarried with another child and living in America, which in itself is painful, but there are also some particularly excruciating moments, like when his new “American” habits present themselves, namely the annoying tendency to call Conor childish names like “Champ” and Sport”:

“‘How you hanging in there, champ?’ his father asked him while they waited for the waitress to bring them their pizzas.

‘Champ?’ Conor asked, raising a skeptical eyebrow.

‘Sorry,’ his father said, smiling bashfully. ‘America is almost a whole different language . . . Your sister’s doing well. Almost walking.’

‘Half-sister,’ Conor said.

‘I can’t wait for you to meet her,’ his father said. ‘We’ll have to arrange for a visit soon. Maybe even this Christmas. Would you like that?’ . . .

Conor ran a hand along the edge of the table. ‘So it’d just be a visit then?’

‘What do you mean?’ his father said, sounding surprised. ‘A visit as opposed to . . .’ He trailed off, and Conor knew he’d worked out what he meant. ‘Conor—’

But Conor suddenly didn’t want him to finish.” (Pg. 86 – 88)

Connor’s grandmother is unnaturally modern, businesslike and independent, treating Conor less like a grandson than just a problem to be dealt with like anything else on a daily basis:

“Conor’s grandma wasn’t like other grandmas. He’d met Lily’s grandma loads of times, and she was how grandmas were supposed to be: crinkly and smily, with white hair and the whole lot. She cooked meals where she made three separate eternally boiled vegetable portions for everybody and would giggle in the corner at Christmas with a small glass of sherry and a paper crown on her head.

Conor’s grandma wore tailored pantsuits, dyed her hair to keep out the gray, and said things that made no sense at all, like “Sixty is the new fifty” or “Classic cars need the most expensive polish.” What did that even mean? She emailed birthday cards, would argue with waiters over wine, and still had a job. Her house was even worse, filled with expensive old things you could never touch, like a clock she wouldn’t even let the cleaning lady dust. Which was another thing. What kind of Grandma had a cleaning lady?

‘Two sugars, no milk,’ she called from the sitting room as Conor made the tea. As if he didn’t know that from the last three thousand times she visited.” (Pg. 39)

School is even worse as everyone is aware of his mother’s illness and treats Conor differently: his classmates ignore and avoid him Harry and his gang bully him, and his teachers feel patronizing even when trying to be sympathetic. And Lily tries to be a good friend to Connor, but the intention feels hollow since it was because she had told one person of his mother that now everyone knows, a transgression for which he feels he could never forgive her.

Connor is not at all fearful of the monster at first and highly skeptical of its purpose behind its storytelling. But the monster is quick to tell him otherwise:

“Conor blinked. Then blinked again. ‘You’re going to tell me stories?’

Indeed, the monster said.

‘Well—’ Conor looked around in disbelief. ‘How is that a nightmare?’

Stories are the wildest things of all, the monster rumbled. Stories chase and bite and hunt.” (Pg. 35)

While the monster’s stories may have simple fairy-tale like beginnings, the characters within, their actions and justifications, prove to be far more complicated than Conor expected—not unlike himself, as the monster ultimately teaches him through pain, love, and personal reflection. In spite of all the apparent lifelessness that permeates this book, life itself is perhaps its most powerful theme. Not only the kind that dictates the natural world but the kind that defines and is defined by humanity as a whole, how we actually live as opposed to how we merely think:

“You were merely wishing for the end of pain, the monster said. Your own pain . . . It is the most human wish of all.

‘I didn’t mean it,’ Conor said.

You did, the monster said, but you also did not.

Conor sniffed and looked up to its face, which was as big as a wall in front of him. ‘How can both be true?’ . . .

The answer is that it does not matter what you think, the monster said, because your mind will contradict itself a hundred times each day . . . Your mind will believe comforting lies while also knowing the painful truths that make those lies necessary. And your mind will punish you for believing both.

‘But how do you fight it?’ Conor asked, his voice rough. ‘How do you fight all the different stuff inside?’

By speaking the truth, the monster said.’” (Pg. 191)

I have not had the pleasure of reading any works from Dowd or Ness, but I can definitely see how they both came to be so beloved in the literary world. I believe I can honestly say that Ness did Dowd and her final idea justice with this hauntingly beautiful tale. This will likely resonate most with those who have had to suffer the emotionally raw and complex pain of losing a loved one, especially when that loss is prolonged but ultimately inevitable.

CREDITS:

All images, audio, and links belong to their respective owners; no copyright infringement is intended.

All book excerpts are from A Monster Calls by Patrick Ness (2013 first U.S. paperback edition; published by Candlewick Press).

MAIN THEME:

“The Call” – Briand Morrison and Roxann Berglund

A Monster Calls is the story of Conor, a 13-year-old boy living in present-day Britain. Ever since his mother was diagnosed with a terrible illness—implied to be cancer due to the descriptions of hair loss and the treatments that sap all her energy—Conor has been suffering from constant nightmares. Or rather, a single nightmare over and over again, involving a black creature with long tenticles glowing eyes that threaten to paralyze and suffocate him. One night, to Conor’s great surprise, he wakes up to find another kind of monster, this one very real and very different, seeming to be made up of branches that “[twist] around one another, always creaking, always groaning”, and “thin, needle-like leaves weaving together to make a green, furry skin that [moves] and [breathes] as there were muscles and lungs underneath” (p. 5). This monster claims to be the very spirit of the earth, most often taking the form of a yew tree. More to the point, it claims that it was summoned by Conor himself, yet the latter can’t recall such a thing. The reason for its coming, says the monster, is to heal Conor (from what Conor has no idea); but in order to do so, the monster must tell Conor three stories from its past travels across the lands of the world, after which Conor tell the monster a fourth in turn: the truth that he has been denying and that he would rather die than admit.

Though this novel was written by Chaos Walking trilogy author Patrick Ness, the idea for it was conceived by Siobhan Dowd, writing activist and author of four young adult novels. She was unfortunately diagnosed with severe terminal breast cancer and, passed away this day in 2007 at the age of 47 before she could further develop the idea. Ness was then contacted by Dowd’s Walker Books editor, Denise Johnstone-Burt (who had previously worked with both writers, though the two never met personally) to put Dowd’s story to paper. To this day, A Monster Calls is the only book whose creators have been awarded both the Carnegie and Kate Greenaway Medals, Ness for literature and Jim Kay for illustration, respectively.

It would be very easy for one seeing this book for the first time to believe it is a horror or suspense story; that’s what I believed at first, and not only because of the title. According to the biography at the back of the book, Kay “used everything from beetles to breadboards to create interesting marks and textures.” Indeed, many of the pictures have a very harsh, scratchy look to them, especially the monster with its thousands of dense clusters of branches and twigs, making it appear all the more wild and imposing, just like nature and the land it embodies and represents. The sky and other environments throughout often appear blotted or streaked, like either a terrible storm is brewing and just waiting to unleash its wrath, or the sky itself is as miserable as the characters in the story and just as unable or unwilling to shed its “tears.” In many scenes, Conor is often depicted as a white silhouette against almost complete blackness, whether it be the monster, his nightmare, or even sometimes the real world, symbolizing to me how the worst aspects of Connor’s reality continually threaten to overwhelm what parts of himself remain and swallow him up. No human faces are ever visually depicted, but on the rare occasion that eyes are shown, like those of the monster or some animal, they are always white with no pupils, either cold and unpredictable or dull and inert.

While this story certainly is frightening to an extent, it is less so in the sense of devilish horror than of pure despair. From Connor’s point of view, the reader gets the sense that he feels he’s the only one who has any faith that his mother will eventually recover, fueling the seemingly justified bitterness that Conor harbors within his heart. While he believes and wishes for his mother’s life more than anything, it is as though the rest of his family is simply giving up and moving on with their own lives while wanting Conor to “be brave” and “talk about what’s going to happen”.

His divorced father is remarried with another child and living in America, which in itself is painful, but there are also some particularly excruciating moments, like when his new “American” habits present themselves, namely the annoying tendency to call Conor childish names like “Champ” and Sport”:

“‘How you hanging in there, champ?’ his father asked him while they waited for the waitress to bring them their pizzas.

‘Champ?’ Conor asked, raising a skeptical eyebrow.

‘Sorry,’ his father said, smiling bashfully. ‘America is almost a whole different language . . . Your sister’s doing well. Almost walking.’

‘Half-sister,’ Conor said.

‘I can’t wait for you to meet her,’ his father said. ‘We’ll have to arrange for a visit soon. Maybe even this Christmas. Would you like that?’ . . .

Conor ran a hand along the edge of the table. ‘So it’d just be a visit then?’

‘What do you mean?’ his father said, sounding surprised. ‘A visit as opposed to . . .’ He trailed off, and Conor knew he’d worked out what he meant. ‘Conor—’

But Conor suddenly didn’t want him to finish.” (Pg. 86 – 88)

Connor’s grandmother is unnaturally modern, businesslike and independent, treating Conor less like a grandson than just a problem to be dealt with like anything else on a daily basis:

“Conor’s grandma wasn’t like other grandmas. He’d met Lily’s grandma loads of times, and she was how grandmas were supposed to be: crinkly and smily, with white hair and the whole lot. She cooked meals where she made three separate eternally boiled vegetable portions for everybody and would giggle in the corner at Christmas with a small glass of sherry and a paper crown on her head.

Conor’s grandma wore tailored pantsuits, dyed her hair to keep out the gray, and said things that made no sense at all, like “Sixty is the new fifty” or “Classic cars need the most expensive polish.” What did that even mean? She emailed birthday cards, would argue with waiters over wine, and still had a job. Her house was even worse, filled with expensive old things you could never touch, like a clock she wouldn’t even let the cleaning lady dust. Which was another thing. What kind of Grandma had a cleaning lady?

‘Two sugars, no milk,’ she called from the sitting room as Conor made the tea. As if he didn’t know that from the last three thousand times she visited.” (Pg. 39)

School is even worse as everyone is aware of his mother’s illness and treats Conor differently: his classmates ignore and avoid him Harry and his gang bully him, and his teachers feel patronizing even when trying to be sympathetic. And Lily tries to be a good friend to Connor, but the intention feels hollow since it was because she had told one person of his mother that now everyone knows, a transgression for which he feels he could never forgive her.

Connor is not at all fearful of the monster at first and highly skeptical of its purpose behind its storytelling. But the monster is quick to tell him otherwise:

“Conor blinked. Then blinked again. ‘You’re going to tell me stories?’

Indeed, the monster said.

‘Well—’ Conor looked around in disbelief. ‘How is that a nightmare?’

Stories are the wildest things of all, the monster rumbled. Stories chase and bite and hunt.” (Pg. 35)

While the monster’s stories may have simple fairy-tale like beginnings, the characters within, their actions and justifications, prove to be far more complicated than Conor expected—not unlike himself, as the monster ultimately teaches him through pain, love, and personal reflection. In spite of all the apparent lifelessness that permeates this book, life itself is perhaps its most powerful theme. Not only the kind that dictates the natural world but the kind that defines and is defined by humanity as a whole, how we actually live as opposed to how we merely think:

“You were merely wishing for the end of pain, the monster said. Your own pain . . . It is the most human wish of all.

‘I didn’t mean it,’ Conor said.

You did, the monster said, but you also did not.

Conor sniffed and looked up to its face, which was as big as a wall in front of him. ‘How can both be true?’ . . .

The answer is that it does not matter what you think, the monster said, because your mind will contradict itself a hundred times each day . . . Your mind will believe comforting lies while also knowing the painful truths that make those lies necessary. And your mind will punish you for believing both.

‘But how do you fight it?’ Conor asked, his voice rough. ‘How do you fight all the different stuff inside?’

By speaking the truth, the monster said.’” (Pg. 191)

I have not had the pleasure of reading any works from Dowd or Ness, but I can definitely see how they both came to be so beloved in the literary world. I believe I can honestly say that Ness did Dowd and her final idea justice with this hauntingly beautiful tale. This will likely resonate most with those who have had to suffer the emotionally raw and complex pain of losing a loved one, especially when that loss is prolonged but ultimately inevitable.

CREDITS:

All images, audio, and links belong to their respective owners; no copyright infringement is intended.

All book excerpts are from A Monster Calls by Patrick Ness (2013 first U.S. paperback edition; published by Candlewick Press).

MAIN THEME:

“The Call” – Briand Morrison and Roxann Berglund

EPISODE SONGS:

“Tadeusz’s Theme” - Paul Gutmann

“Tadeusz’s Theme” - Paul Gutmann

“Desesperación” - The Curellis

“My Strength You Are…Variations and Improvisations on an Eternal Theme” - Thomas Wayne King

Download the full 15-minute episode here!

A Monster Calls on Wikipedia

Siobhan Dowd on Wikipedia

The Siobhan Dowd Trust

Patrick Ness on Wikipedia

Patrick Ness's Official Website

Jim Kay's Official Website

A Monster Calls on Common Sense Media

Buy A Monster Calls on Amazon

Buy A Monster Calls on Barnes & Noble

Buy A Monster Calls on Ebay

^^ Back to Books, Graphic Novels, and Other Works of Literature

A Monster Calls on Wikipedia

Siobhan Dowd on Wikipedia

The Siobhan Dowd Trust

Patrick Ness on Wikipedia

Patrick Ness's Official Website

Jim Kay's Official Website

A Monster Calls on Common Sense Media

Buy A Monster Calls on Amazon

Buy A Monster Calls on Barnes & Noble

Buy A Monster Calls on Ebay

^^ Back to Books, Graphic Novels, and Other Works of Literature